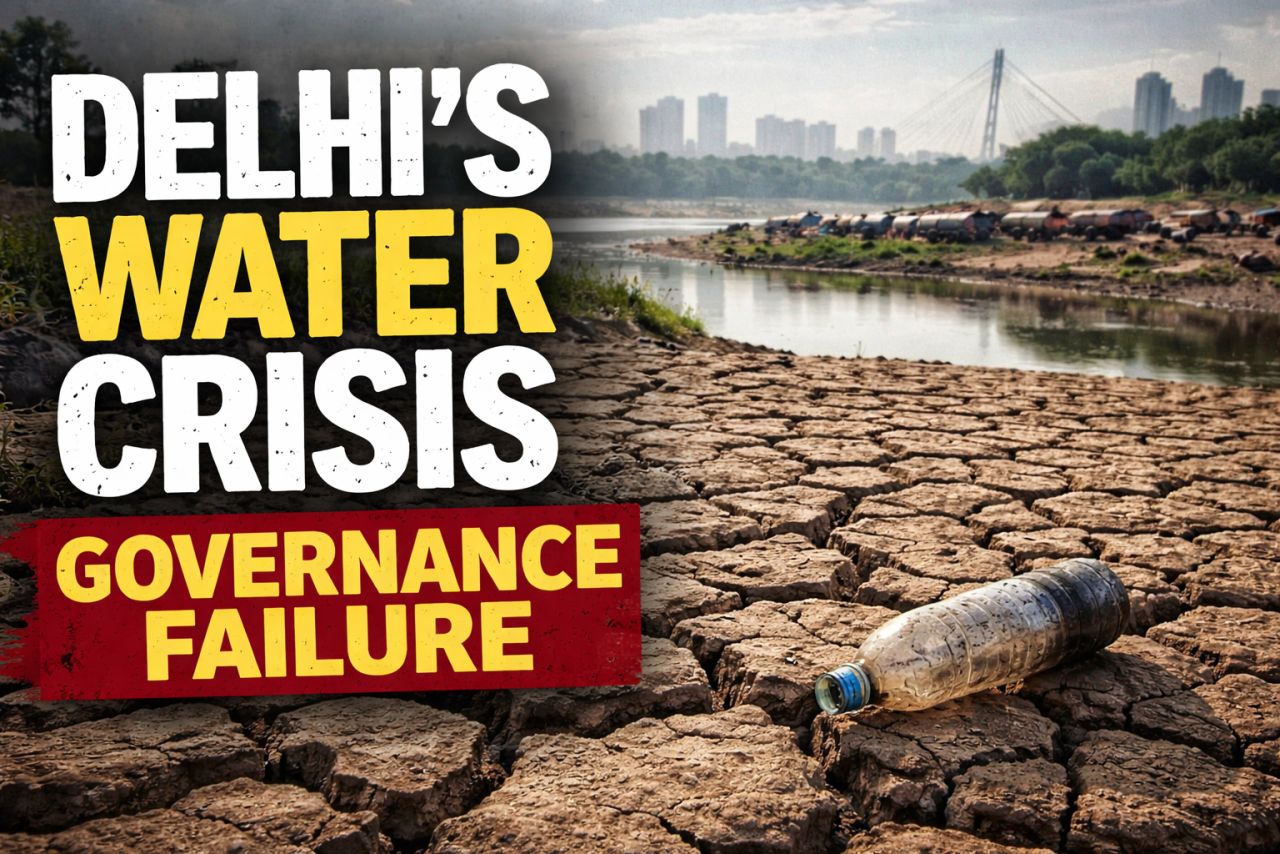

Delhi’s water crisis did not happen by accident. It was built over decades of neglect.

Delhi is not running out of water because it lacks rainfall or rivers. It is running out of water because it has systematically weakened the systems meant to capture, store, clean, and govern it.

What the capital is experiencing today is not an unexpected environmental emergency but the predictable outcome of decades of policy drift, fragmented responsibility, and short-term urban planning. The crisis did not arrive overnight, nor is it driven by nature alone. It is largely man-made—and therefore preventable.

A River City That Forgot How to Manage Water

Delhi’s geography once made it naturally resilient. The Yamuna flowed through the city, supported by a dense network of lakes, wetlands, ponds, stepwells, and floodplains. These were not aesthetic features; they were functional infrastructure designed to absorb monsoon rain, prevent floods, and recharge groundwater.

Over time, urban expansion treated these water bodies as expendable land. Lakes were filled or converted into manicured parks that no longer hold water. Natural drains were encased in concrete. Floodplains were encroached upon. What remained lost its ecological function.

Today, many of Delhi’s water bodies lie dry for most of the year, their beds overtaken by weeds, debris, or informal use. Their collapse has broken the natural cycle that once sustained the city’s water balance.

External Dependence and a Polluted Lifeline

As local water systems weakened, Delhi grew increasingly dependent on water drawn from outside its borders. The city now relies heavily on inter-state river-sharing arrangements, turning water into a fragile political resource.

Any problem upstream, such as less water, delayed supply, or disputes, quickly leads to shortages in Delhi. As a result, summer water scarcity has become routine, exposing how risky this dependence has become.

At the same time, Delhi has failed to protect the river that flows through it. The Yamuna enters the city with relatively manageable pollution levels and exits as one of the most contaminated river stretches in the country. Despite decades of investment in sewage treatment infrastructure, untreated waste continues to enter the river due to incomplete sewer networks, illegal connections, and weak enforcement.

A city that cannot safeguard its own river cannot ensure long-term water security.

Groundwater: The Invisible Emergency

Groundwater has become Delhi’s silent lifeline and its most serious vulnerability.

As surface water sources declined, borewells multiplied across residential colonies, commercial complexes, and construction sites. What was once an emergency backup has turned into the primary water source for large parts of the city.

This reliance has pushed groundwater extraction far beyond sustainable limits. Water tables are falling rapidly in many areas, forcing wells to be drilled deeper each year. Several zones are now officially classified as over-exploited or critical.

Recharge mechanisms such as rainwater harvesting exist in regulation but remain poorly enforced. Monitoring is weak, data is fragmented, and violations rarely invite penalties. Groundwater depletion, largely invisible to the public, continues unchecked.

Delhi is consuming water faster than nature can replenish it.

Too Many Authorities, Too Little Accountability

Perhaps the most telling feature of Delhi’s water crisis is that it persists despite an abundance of laws, policies, and institutions.

Multiple agencies oversee water supply, wastewater treatment, wetlands, lakes, and drainage. In theory, this should ensure comprehensive management. In practice, it results in overlapping mandates, blurred responsibility, and delayed action.

Water bodies are identified but not protected. Restoration plans are announced but left incomplete. Encroachments persist while files move between departments. Deadlines pass without consequence.

The problem is not the absence of rules—it is the absence of enforcement and accountability.

Climate Change Exposes the Cracks

Climate change has intensified the consequences of poor governance.

Rainfall patterns have become increasingly erratic. Short, intense downpours overwhelm the city because natural drainage systems no longer function. When the rains stop, the city slips back into scarcity because there are too few water bodies left to store excess water.

Rising temperatures increase demand and accelerate evaporation. Heatwaves strain already fragile supply systems, particularly in areas dependent on tankers or informal sources.

Climate stress did not create Delhi’s water crisis, but it has magnified every existing failure.

Water Scarcity and Urban Inequality

Delhi’s water crisis is not evenly distributed.

Affluent neighbourhoods manage scarcity through storage tanks, private borewells, and paid services. Informal settlements and unauthorised colonies depend on erratic tanker supplies or distant community taps, often spending hours each day securing water.

This inequality has direct consequences for health, sanitation, education, and livelihoods. Water scarcity deepens urban poverty and disproportionately affects women and children.

A city cannot claim progress when access to water depends on income and location.

Why Emergency Fixes Keep Failing

Policy responses continue to focus on short-term measures—tankers, temporary restrictions, and seasonal appeals for conservation. While necessary in moments of crisis, these steps do not address structural weaknesses.

Long-term resilience requires restoring local water systems. Lakes must hold water year-round, not merely appear green. Wetlands must be protected as ecological assets, not treated as development obstacles. Sewage must be intercepted before it reaches rivers and drains.

Rainwater harvesting must move beyond token compliance. Groundwater extraction must be monitored and regulated with real consequences for violations. Above all, water governance must be unified, transparent, and accountable.

A Crisis of Choice, Not Chance

Delhi’s drying lakes, polluted rivers, and falling water tables are not isolated environmental failures. They are symptoms of governance choices made over decades.

The capital is exhausting the systems that once sustained it while relying on external sources that grow more uncertain each year. Without decisive action, water scarcity will shift from a seasonal challenge to a permanent constraint.

Delhi’s water crisis is not natural.

It is the result of neglect and therefore within the power of governance to fix.