Time is often described as a healer, but for many people, it never truly is. What it offers instead is something quieter and more difficult to name—the ability to live alongside pain without being consumed by it.

Across spiritual traditions, there is a quiet but radical idea that suffering is not meant to be cured. It is meant to be lived with. In Buddhism, the concept of dukkha recognizes suffering as an unavoidable part of being human. The solution is not to erase pain, but to change how we relate to it. Instead of resisting the ache, we learn to carry it with awareness and compassion.

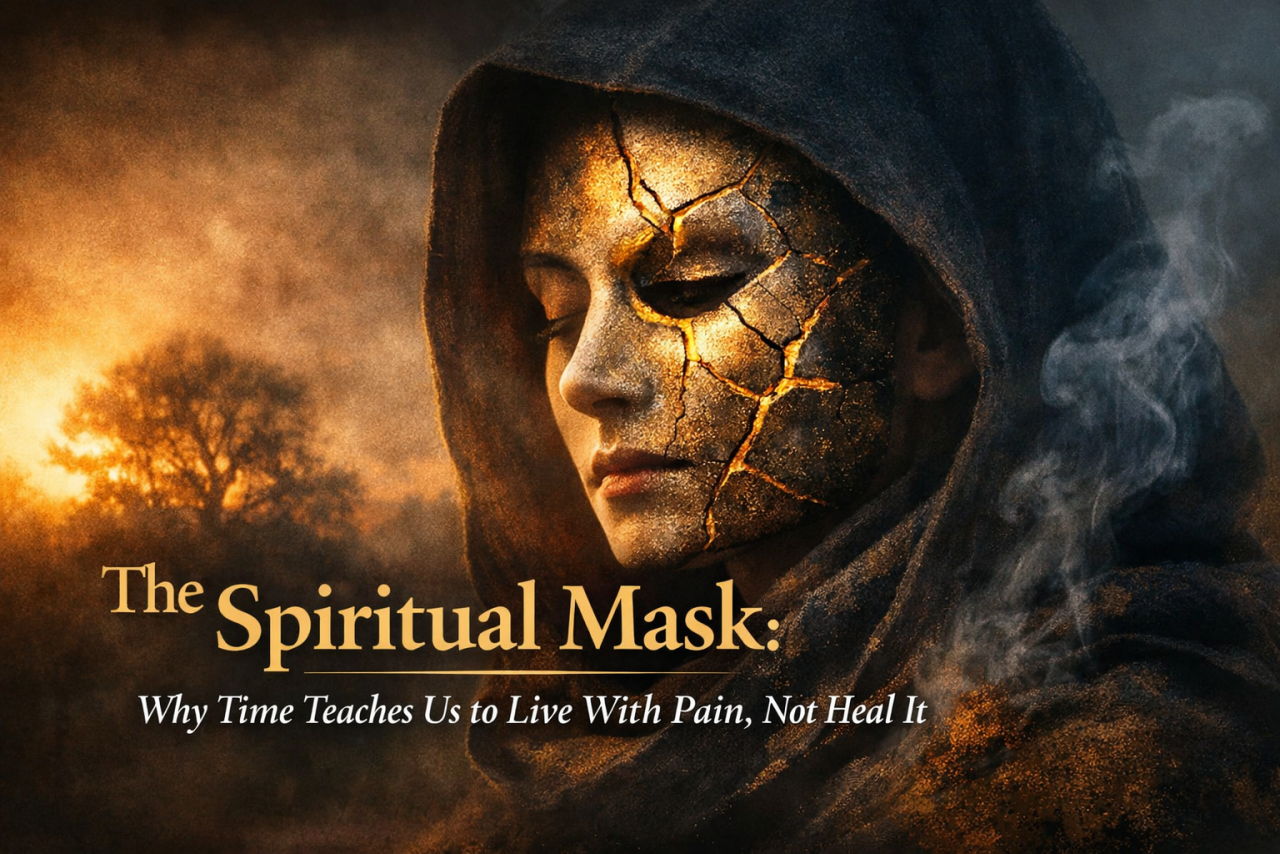

Over time, this shift often looks like pretense. But this pretense is not deception. It is a skill. Time teaches us how to walk with grief without collapsing under its weight, how to speak about loss without being undone by it. This kind of pretending is not hypocrisy; it is a form of emotional armor. It allows people to move through daily life without spilling their wounds onto everyone around them. Slowly, time shows us how to hold broken pieces without injuring ourselves on their sharp edges, how to appear whole long enough for something steadier to take shape inside.

Literature has long understood this truth. Its most enduring characters are not healed by time; they are shaped by it. Their survival lies not in forgetting pain but in learning how to live alongside it.

In Beloved, Toni Morrison’s Sethe carries the scars of slavery on her back, described as a “chokecherry tree.” These wounds do not fade with years. They remain alive, just as her past returns in the form of a ghost that refuses to stay buried. Time does not heal Sethe’s trauma. Instead, it teaches her how to exist beside it, how to perform normalcy until moments of fragile grace become possible. Her endurance is not a story of recovery, but of coexistence with pain.

The same pattern appears in Homer’s The Iliad. Achilles does not emerge healed from his grief over Patroclus’s death. The epic ends not with peace, but with ritual. There is a funeral, a temporary truce, and an understanding that war and loss will continue to echo through memory. Achilles’ rage is not resolved; it is transformed into ceremony. His grief becomes structured, contained, and shared. It is a collective act of pretending that order has been restored, even as everyone knows it has not.

Joseph Conrad’s Heart of Darkness offers a more unsettling version of this lesson. Kurtz’s moral collapse is not reversed by time. Instead, it is Marlowe who must carry the weight of what he has witnessed back into the civilized world. When he lies to Kurtz’s Intended about the nature of Kurtz’s death, the lie functions as a survival mechanism. It protects her, but it also protects Marlowe from a truth too corrosive to release unchecked. Time does not absolve him; it trains him to deliver the lie with calm composure.

These characters do not move on from pain. They adapt to it. They learn how to stand, how to speak, how to breathe with an invisible weight pressing against their chest. What time offers them is not healing, but habituation. Pain becomes familiar terrain rather than an open wound.

For modern life, this understanding can be quietly liberating. It frees people from waiting for time to perform a miracle it was never meant to deliver. The aim is not a pain-free existence, but an integrated one. Living well does not require wholeness; it requires participation.

Engaging with life while still broken is not denial. It is courage. Listening to the body’s fatigue or recurring ache can become an act of recognition rather than frustration, a way of asking which old wound is asking to be acknowledged. Integration, rather than erasure, becomes the goal. Like the Japanese art of kintsugi, where cracks are filled with gold instead of hidden, the marks of damage become part of the design.

Time, then, is not a healer. It is a relentless and patient teacher. It teaches the oldest human skill of all: how to live with what cannot be fixed. It trains people in the performance of being okay, day after day, until the performance slowly stops feeling like an act. Without announcement or ceremony, it becomes a tribute—to the pain that shaped a person, and to the enduring self that learned how to carry it.