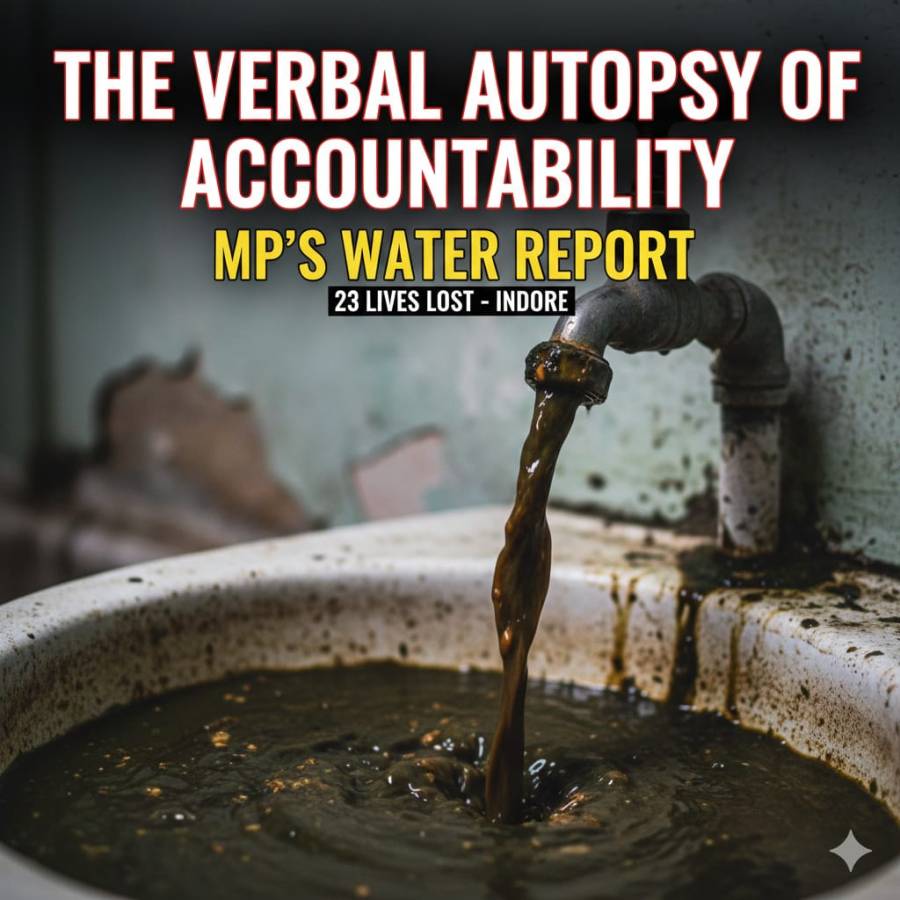

In the corridors of power, language is often used as a cloak—a way to soften the blow of failure or to shroud negligence in the garb of "technical procedure." But every so often, the judiciary acts as a sharp lens, focusing on these linguistic gymnastics until the underlying apathy is scorched into plain view.

This week, the Indore bench of the Madhya Pradesh High Court did exactly that. Faced with a state government report on the tragic deaths in Bhagirathpura, Justices Vijay Kumar Shukla and Alok Awasthi didn’t just read the document; they dismantled it. At the heart of their ire was a single, jarring phrase: “Verbal Autopsy.”

A Semantic Shield for Systemic Failure

When 23 lives are snuffed out because the water coming out of their taps was a "polymicrobial mix" of E. coli, Salmonella, and Vibrio cholera, the public expects science, rigor, and accountability. Instead, the MP government offered a "death audit" that sounded more like a creative writing exercise than a medical investigation.

The court’s question was as biting as it was necessary:

“Is verbal autopsy a medical term or a term coined by the state government?”

In truth, while "verbal autopsy" is a recognized public health research tool used in data-scarce regions to determine trends, the state’s application of it here was a masterclass in obfuscation. By using "verbal" instead of "clinical," the administration essentially admitted it lacked the forensic evidence to back its claims. It was an "eyewash"—a desperate attempt to categorize deaths as "inconclusive" or "unrelated" without the backbone of an actual post-mortem.

The Cleanest City’s Dirty Secret

There is a tragic irony in the fact that this crisis unfolded in Indore—a city that wears its "Cleanest City in India" tag like a badge of honor. But as the High Court rightly noted, cleanliness is not merely about sweeping the streets; it is about the integrity of the infrastructure beneath them.

The investigation revealed a nightmare scenario: a leakage in the Narmada water pipeline allowed raw sewage to seep into the drinking supply. For weeks, the residents of Bhagirathpura were essentially being poisoned by the very system designed to sustain them.

The government’s response, however, was not one of urgent contrition but of statistical containment. By acknowledging only 16 deaths and dismissing the rest through the aforementioned "verbal" gymnastics, the state attempted to minimize a tragedy that local residents claim has claimed nearly 30 lives. The court saw through this immediately, labeling the government’s approach as "insensitive" and "vague."

Why "Inconclusive" Is Inacceptable

The state’s report suggested that while 16 deaths were linked to the epidemic, others were "inconclusive." In a legal and moral sense, "inconclusive" is the ultimate escape hatch. It allows the administration to avoid paying compensation, skip disciplinary action against specific officials, and ultimately, bury the file.

The High Court’s refusal to accept this narrative is a victory for the Right to Life under Article 21. By appointing a one-man commission headed by a former HC judge, the court has signaled that the state can no longer be the judge of its own cause.

"Nobody feels that we are drinking safe water these days," the bench remarked—a chilling indictment of a government that has prioritized optics over the literal lifeblood of its citizens.

The High Cost of Callousness

The "callous approach" exposed here isn't just about a broken pipe; it’s about a broken trust.

- Budgetary Negligence: It was revealed that proposals for new pipelines had been stalled since 2022 due to "fund shortages."

- Delayed Response: Symptoms were reported as early as late December, yet the "epidemic" declaration and serious intervention only followed judicial prodding.

- Accountability Deficit: While the state gave "verbal" explanations, the residents of Bhagirathpura were left with very real, very physical grief.

Final Take: Beyond the Paper Trail

A "verbal autopsy" cannot bring back the dead, nor can it sanitize the reputation of an administration that allowed sewage to flow into kitchens. The Madhya Pradesh government must realize that the judiciary will not be satisfied with reports that are scientifically hollow and emotionally bankrupt.

The intervention of the High Court is a reminder that when the executive fails to protect the most basic fundamental right—the right to clean water—the law must step in to perform an autopsy of a different kind: a forensic examination of governance itself.