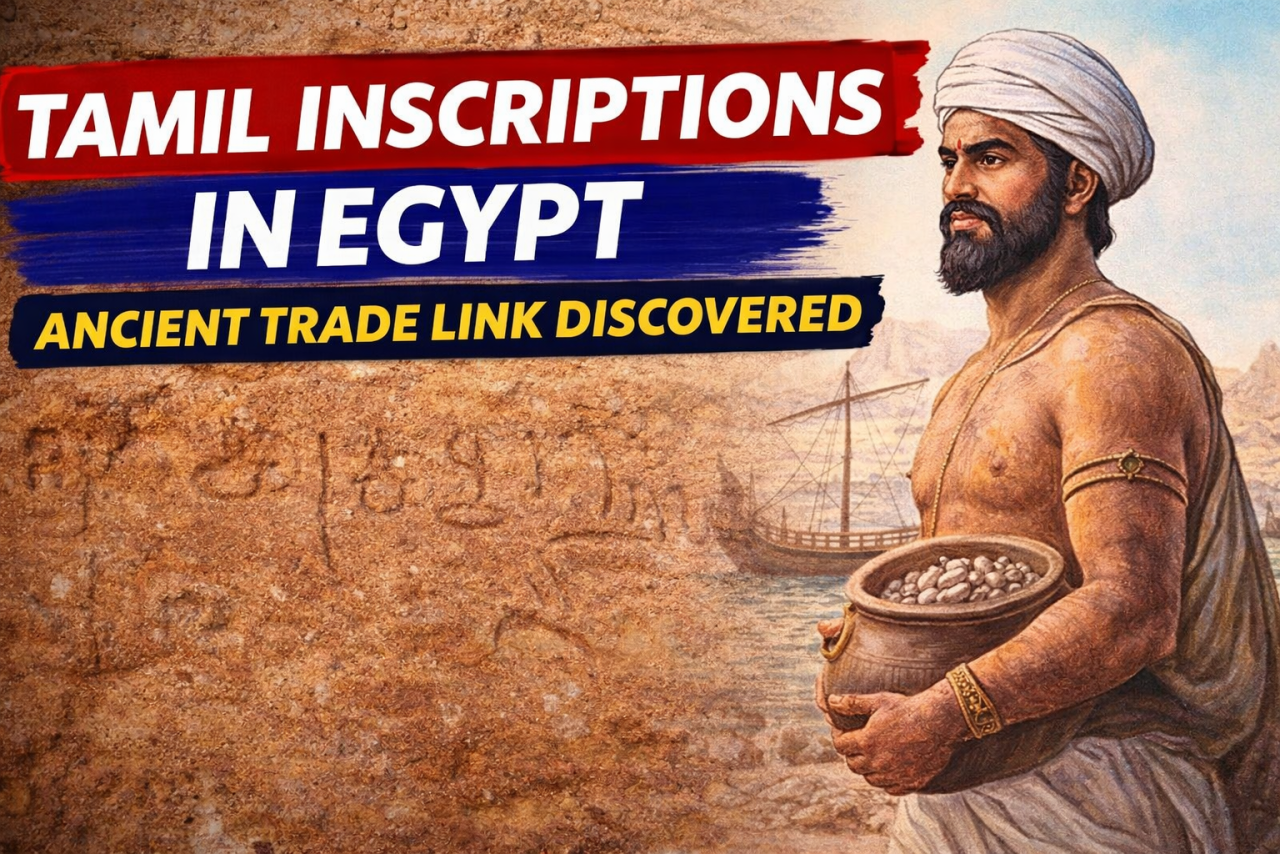

Nearly 2,000 years ago, Tamil traders crossed the seas and left their names carved in Egyptian stone — a discovery that is now rewriting the history of India’s ancient global connections.

Recent findings of Tamil Brahmi inscriptions in Egypt have added fresh evidence to the history of early maritime trade between South India and the Mediterranean world. These inscriptions, discovered at ancient Egyptian sites, suggest that Tamil-speaking merchants were present in the region nearly two thousand years ago. The discovery strengthens earlier claims that trade between the Tamil region and the Roman Empire was active and well organized during the early centuries of the Common Era.

Tamil Brahmi is one of the earliest scripts used to write the Tamil language. It dates from around the 3rd century BCE to the early centuries CE. The script has been found mainly in Tamil Nadu and parts of Sri Lanka, usually in caves, on pottery, and on trade-related objects. The appearance of Tamil Brahmi inscriptions in Egypt shows that Tamil merchants did not remain limited to the Indian Ocean region but travelled as far as North Africa.

The inscriptions were found on the walls of ancient structures and on pottery fragments. Some of them contain personal names written in Tamil Brahmi. One such name appears to be “Korran” or “Kotra,” which is linked to Tamil naming traditions. The repetition of such names suggests that these were not random markings but deliberate inscriptions left by Tamil individuals. Scholars believe that these inscriptions were made by merchants who were involved in long-distance trade.

Historical records already point to strong trade links between the Tamil region and the Roman Empire. Classical texts such as the Periplus of the Erythraean Sea, written in the first century CE, describe active trade between Indian ports and Egyptian ports like Berenike and Myos Hormos. These ports served as important centres for goods moving between India and the Mediterranean. Archaeological excavations in these regions have uncovered Roman coins, amphorae, beads, and Indian pottery, showing a two-way exchange of goods.

From South India, traders exported spices, especially black pepper, along with pearls, ivory, precious stones, textiles, and aromatics. In return, they imported gold, silver, wine, and glassware from the Roman world. Tamil literature of the Sangam period also refers to Yavana traders, a term used for Greeks and Romans, who visited Tamil ports. Poems describe ships arriving with gold and leaving with pepper and other goods. These literary references match well with the material evidence found in Egypt.

The Tamil Brahmi inscriptions in Egypt help to humanize this trade network. Instead of only objects and coins, we now have names written by individuals. These names suggest that Tamil merchants may have stayed for long periods in Egyptian ports. They likely formed small communities, maintained their language, and left marks of their presence. Writing one’s name on a wall or object may have been a way to record identity in a distant land.

The script style of these inscriptions has been studied carefully. Scholars compare the letter forms with known Tamil Brahmi inscriptions from Tamil Nadu. Based on these comparisons, the Egyptian inscriptions are dated to roughly the early centuries CE. This dating fits well with the peak period of Indo-Roman trade. It shows that contact was not indirect but involved physical movement of people across long sea routes.

The discovery also highlights the importance of the Red Sea region as a meeting point of cultures. Egyptian ports connected the Mediterranean with the Indian Ocean through well-established sea routes. Monsoon winds allowed ships to travel directly between the west coast of India and the Red Sea. This knowledge of seasonal winds made regular trade possible and reduced travel time. Tamil merchants would have been familiar with these routes and navigational patterns.

These findings encourage a broader understanding of early globalization. Trade was not limited to goods; it included movement of language, ideas, and cultural practices. The presence of Tamil writing in Egypt shows that Indian merchants were confident enough to leave written records abroad. It also shows that ancient societies were more interconnected than often assumed.

The Tamil Brahmi inscriptions in Egypt do not stand alone. They add to a growing body of archaeological and literary evidence that supports the idea of strong maritime networks linking South India with the wider world. Together, inscriptions, coins, pottery, and classical texts form a consistent picture of sustained contact.

This discovery deepens our knowledge of early Indian history and places Tamil traders firmly within global trade networks of the ancient world. It reminds us that long before modern globalization, people from the Indian subcontinent were already part of international exchange systems that linked Asia, Africa, and Europe.