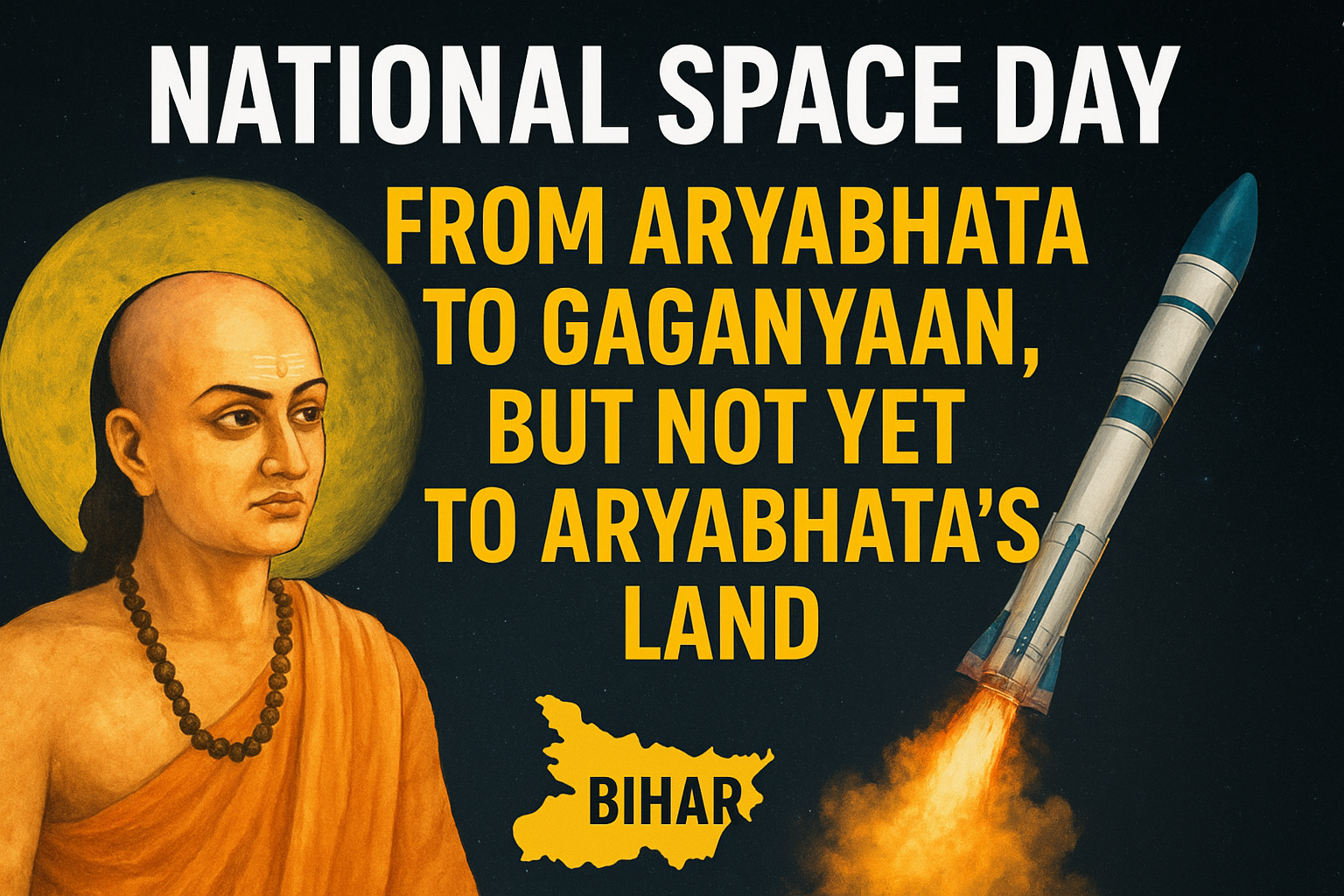

India celebrates National Space Day on 23 August to mark the soft landing of Chandrayaan-3. This year’s theme is “From Aryabhata to Gaganyaan,” a line that connects our ancient knowledge with India’s first human spaceflight mission. The Prime Minister’s address highlighted the same theme and called it a bridge between past confidence and future resolve

The theme invites us to remember Aryabhata, the mathematician and astronomer who lived in the fifth century. His work explained the motion of planets, the value of pi with striking accuracy, and the idea that Earth rotates on its axis. Historical sources agree that he lived and worked at Kusumapura, identified with Pataliputra, which is modern-day Patna. Many accounts also link him with an observatory at the Sun Temple in Taregana near Patna.

If we trace the journey “from Aryabhata to Gaganyaan,” we meet several proud milestones. India named its first satellite Aryabhata in 1975. Since then ISRO has built a strong national network. There is the Vikram Sarabhai Space Centre in Thiruvananthapuram, the Satish Dhawan Space Centre at Sriharikota for launches, the U R Rao Satellite Centre in Bengaluru, tracking and control units across the country, and many other facilities. This spread shows how India built capacity step by step.

Yet the map has a clear gap. There is no ISRO space centre in Patna or elsewhere in Bihar, the region most closely linked with Aryabhata’s life and work. A research institute named after him does exist, but it is in Nainital, Uttarakhand. It is ARIES, the Aryabhatta Research Institute of Observational Sciences, and it contributes to astronomy from the Himalayan foothills. While ARIES is an asset for the country, it does not change the fact that Bihar, with its deep connection to Aryabhata, lacks a major space or astronomy hub.

This absence is more than a missing dot on a map. Education grows when history, place, and opportunity meet. Taregana was chosen by many observers as a prime viewing point for the 2009 total solar eclipse. That event drew scientists, students, and tourists. It showed how a site in Bihar can turn into a classroom under the open sky when the right support is present.

National Space Day aims to inspire young minds. Newspapers and speeches this year underline how India has reached the Moon and Mars, and how missions like Gaganyaan will carry our astronauts to space. The message is that science belongs to all Indians and that every child can dream of the stars. If that is our goal, then the land associated with Aryabhata deserves a living, visible link to the space program.

What could that link look like? It need not begin with a rocket complex. India could start with a National Aryabhata Centre in or near Patna. Such a centre could combine a high-quality planetarium, a hands-on science museum, a small optical observatory for schools, and a public data lab where students explore satellite images and weather maps. It could host lectures and science festivals every year on National Space Day. Exhibits could tell the story of ancient Indian astronomy, including Aryabhata’s mathematics, alongside models of PSLV and GSLV rockets. This would connect “then” and “now” in a way that a textbook cannot.

The centre could also build a network of school clubs across Bihar. Teachers would receive training in observational projects such as tracking the phases of the Moon, measuring shadows to estimate Earth’s tilt, and using low-cost spectroscopes. Students could analyse images from Indian satellites to study floods in the Ganga basin or crop patterns in their districts. Local relevance would make space science feel useful and real.

Taregana deserves special attention. The Sun Temple site linked with Aryabhata offers a unique setting for an upgraded community observatory. Clear signage, safe viewing platforms, and regular sky-watch nights would attract families and tourists. During eclipses, meteor showers, and planetary conjunctions, the site could become a learning hub. Coordinating with ISRO and the National Council of Science Museums would help maintain scientific quality and public safety.

There is also a powerful symbolic step. When ISRO names future student programs, scholarships, or small satellites, some of those names could honour places tied to India’s scientific heritage. A “Kusumapura Student Satellite Challenge” or a “Taregana Eclipse School” would signal that knowledge is not limited to big cities.

Critics may say that India already supports many centres and must focus resources where telescopes and launch pads work best. That point is fair. Launch sites need coastal safety zones and special logistics. Big observatories need clear, high skies. But none of this rules out a strong educational and outreach presence in Aryabhata’s land. A well designed planetarium and data lab cost far less than a launch range and can still change thousands of young lives each year.

On National Space Day we celebrate our journey from the first satellite to human spaceflight. The theme “From Aryabhata to Gaganyaan” is more than a slogan. It is an invitation to tie our modern achievements to the places and people who began India’s scientific story. Establishing a visible, permanent space-science presence in Bihar would honour that story. It would tell every child in the region that the sky is not far away and that the path from Patna to the stars is open to them.

If India accepts this challenge, then on a future National Space Day students in Patna and Taregana will not only read Aryabhata’s name in a chapter. They will look up through a telescope, download satellite data, and feel that they stand where India’s space story began.