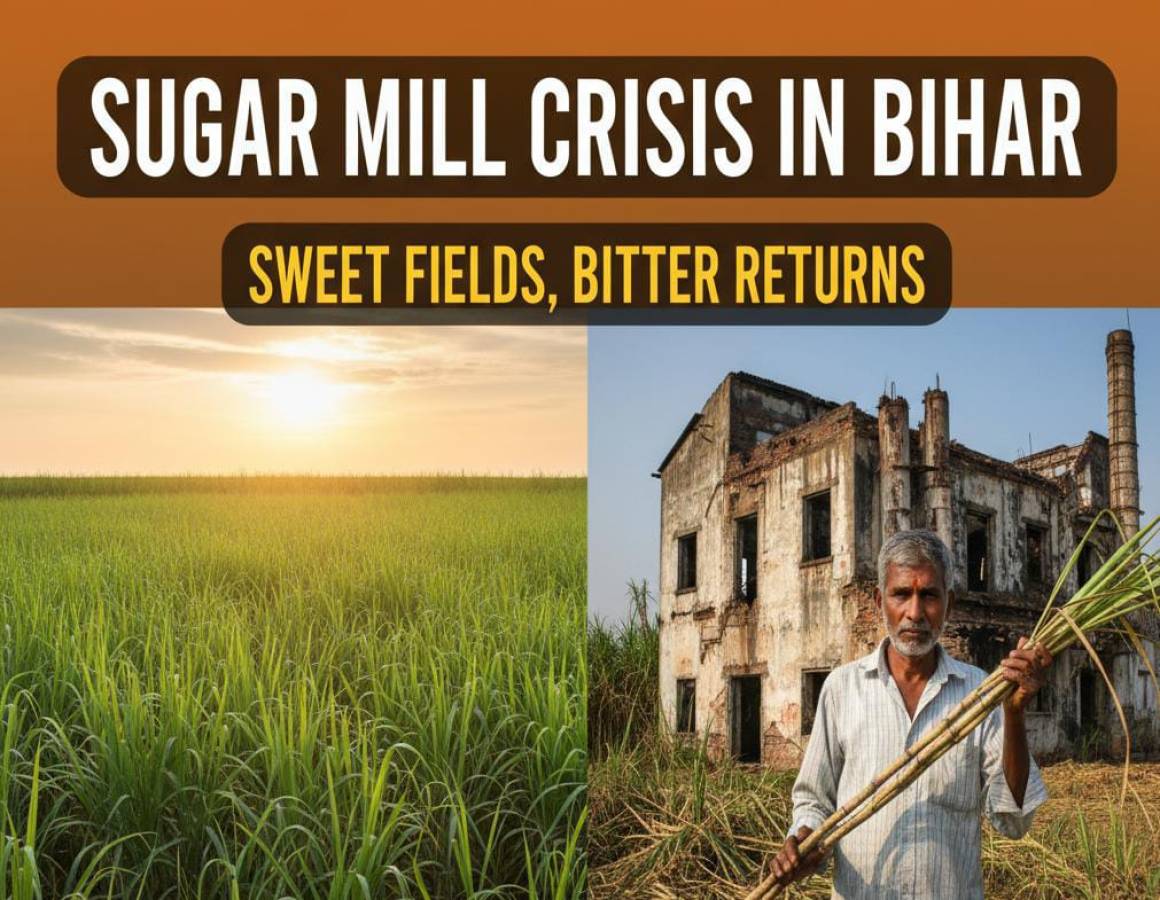

There was a time when the faint, sweet scent of sugarcane juice was part of Bihar’s countryside air. From Champaran to Samastipur, the chimneys of sugar mills rose like proud symbols of rural prosperity. Entire villages revolved around the rhythm of the mills from cane cutting at dawn to bullock carts queuing at the gates by dusk. But today, much of that sweetness has turned bitter. The once-thriving sugar industry of Bihar lies in crisis, and its decline tells a larger story about how neglect and shortsighted policies can hollow out a region’s economic core.

In the years following Independence, Bihar was among India’s leading sugar-producing states. The Gangetic plains were ideal for sugarcane cultivation, and the region’s mills — many set up under British rule — became the backbone of local economies. They didn’t just produce sugar; they generated jobs, supported transport networks, and kept village markets alive. But over the decades, as other states like Uttar Pradesh and Maharashtra modernized their mills and diversified into ethanol and power generation, Bihar was left behind.

Today, according to the state’s Cane and Sugarcane Development Department, only nine sugar mills are operational, with a combined crushing capacity of about 62,950 tonnes per day. The rest — once scattered across East and West Champaran, Sitamarhi, and Gopalganj — have either shut down or operate at a fraction of their old strength. What this means for farmers is painfully clear: fewer buyers, longer distances to sell their cane, and lower returns.

A sugarcane farmer in Gopalganj put it bluntly in a local meeting last month: “Pehle hum khet se mill tak gaana le jaate the, ab mil hi band ho gaya.” (Earlier we took our cane straight to the mill; now the mill itself is closed.) What remains of Bihar’s sugar sector survives largely on government life support. The state recently had to release ₹51.31 crore in pending payments to farmers linked to Riga Sugar Company — one of the few surviving units — just to prevent a complete breakdown of trust between growers and mill owners.

The deeper problem is structural. Sugar mills operate in a tricky balance of economics: they must pay farmers a Fair and Remunerative Price (FRP) fixed by the Centre, even when the selling price of sugar fluctuates. When sugar prices fall, as they did in late 2024 — touching an 18-month low — mills face a liquidity crunch. They can’t pay farmers on time, and farmers, already battling rising input costs, sink further into debt.

States like Maharashtra have managed to survive this cycle by diversifying. Ethanol production, co-generation of electricity, and the sale of by-products like molasses have cushioned them. But Bihar’s mills have not kept pace. Ethanol blending is still minimal, and power generation from bagasse is rare. In a state where infrastructure is already fragile, these missed opportunities have proved costly.

Industry experts also point to policy inertia. The 15-kilometre distance rule between two mills, originally meant to prevent overcompetition, now acts as a straitjacket. It stops smaller, modern mills from coming up, forcing farmers to depend on a handful of large factories. Meanwhile, the cooperative movement — once the pride of Bihar’s rural economy — has weakened under political meddling and mismanagement.

Yet, all is not lost. Bihar’s soil still produces some of the finest sugarcane in India. Farmers are hardworking and resilient, and the government has shown occasional intent to revive the sector. The Centre’s push for ethanol blending could offer a fresh lifeline if Bihar can attract investment in distilleries. Smaller khandsari and jaggery units, which consume nearly a third of the state’s cane, can also be modernized to create local value and jobs.

The sugar mill crisis is more than an economic issue — it is a story about rural India’s broken promises. When a mill closes, it doesn’t just stop crushing cane; it crushes livelihoods, too. The chai shops nearby see fewer customers, the cycle repairman loses work, and the transporter who carried cane loads to the mill must now look for work elsewhere.

If Bihar is serious about reviving its rural economy, the sugar industry must be at the heart of that effort. It needs a mix of fresh investment, fair pricing, ethanol integration, and political will. The sweetness can return — but only if the state chooses to look beyond nostalgia and treat sugarcane not as an old story, but as a new opportunity.

Because for millions of farmers across the plains of Bihar, it isn’t just about sugar. It’s about dignity, survival, and the right to taste prosperity again.