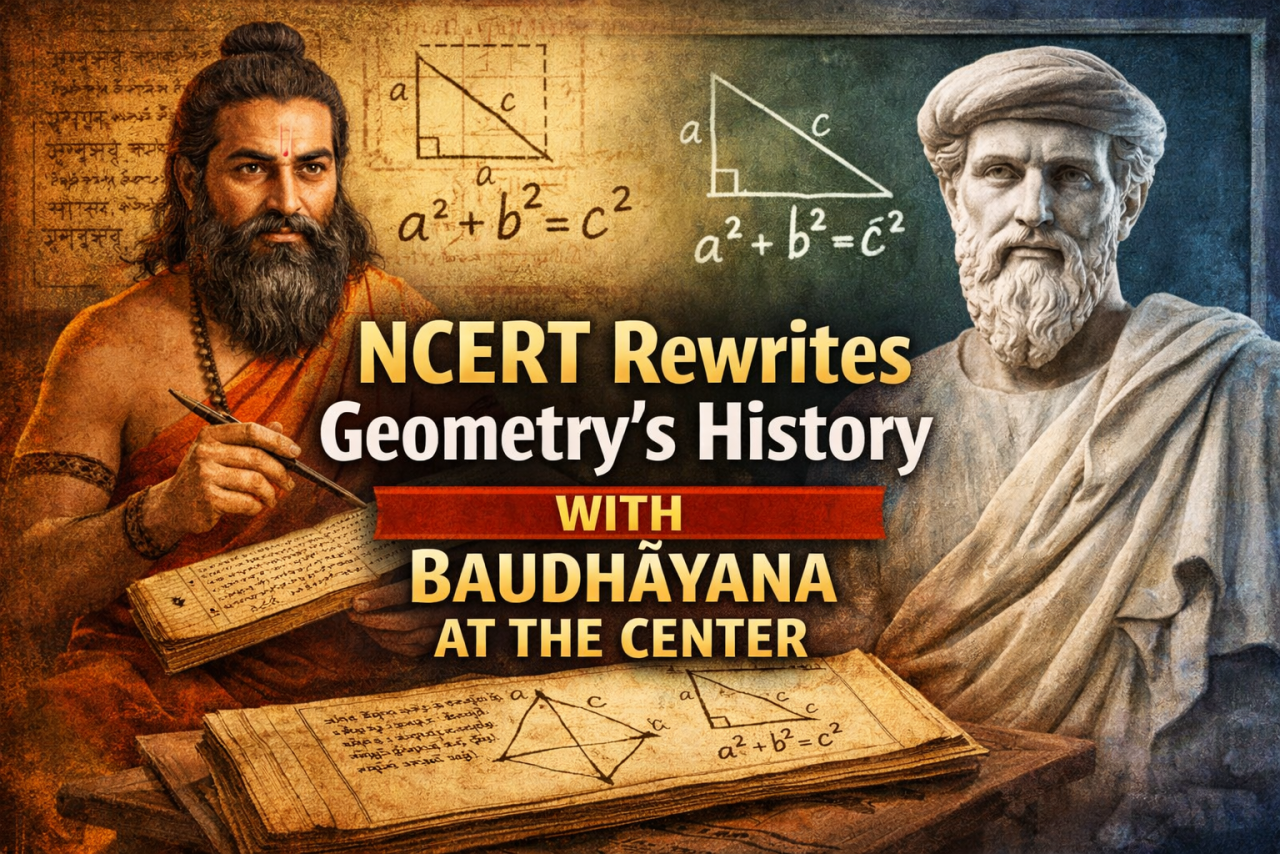

For most students, the formula a² + b² = c² is learned early and remembered for life. It is almost always introduced as the Pythagoras theorem, named after the Greek philosopher Pythagoras. From school classrooms to competitive exams, generations have grown up believing that this fundamental idea of geometry originated in ancient Greece. However, a recent change in India’s school curriculum is prompting students to look at this familiar equation from a very different historical perspective.

According to the latest Class 8 NCERT mathematics textbook, Ganita Prakash, the idea behind the theorem was first clearly stated by the ancient Indian mathematician Baudhāyana, who lived around 800 BCE. This places his work nearly three centuries before Pythagoras, who is believed to have lived around 500 BCE. The textbook explains that Baudhāyana did not merely use the idea in practice but also described it clearly in written form, making him one of the earliest known figures to formalize this geometric relationship.

Baudhāyana’s work appears in the Baudhāyana Sulba Sutra, a collection of ancient texts associated with Vedic rituals and altar construction. These texts show that geometry in ancient India was not abstract or decorative but deeply practical. Measurements were needed to design precise fire altars, and geometric rules were developed to ensure accuracy. One of the most striking statements from the Sulba Sutra explains that the diagonal of a square produces an area twice that of the original square. This observation directly reflects the logic behind what we now call the Pythagoras theorem.

The NCERT textbook explains that this insight forms the basis of understanding right-angled triangles, where the square of the longest side equals the sum of the squares of the other two sides. To help students relate to the idea, the book also discusses number sets that satisfy this relationship, such as (3, 4, 5) and (5, 12, 13). These are commonly known as Pythagorean triples, but the text points out that Baudhāyana had already identified such combinations centuries earlier.

Rather than removing Pythagoras from the story, the textbook uses the term “Baudhāyana–Pythagoras theorem.” This approach allows students to connect what they already know with a broader historical context. It also reflects how mathematical knowledge often develops across civilizations, with ideas traveling, evolving, and being rediscovered over time.

What makes this update especially interesting is how far the influence of these early ideas may have reached. The textbook suggests that the study of such numerical patterns eventually inspired later mathematicians, including Pierre de Fermat in the 17th century. Fermat’s famous Last Theorem, which puzzled mathematicians for more than 300 years before being solved in 1994, grew out of the same basic curiosity about whole-number solutions to geometric equations. This shows how a concept first explored in ancient India may have contributed to a much longer global journey of mathematical discovery.

For students today, this change is not just about correcting a historical record. It encourages a broader understanding of where knowledge comes from. Senior mathematician Eknath Ghate of the Tata Institute of Fundamental Research has noted that these claims are reasonable and supported by historical evidence. Recognizing such contributions helps students see mathematics as a shared human effort rather than the achievement of one culture or era.

Learning that advanced mathematical thinking existed in India thousands of years ago can also change how students relate to the subject. It builds confidence and curiosity, showing that ideas developed locally can have global significance. As students continue to study geometry, seeing Baudhāyana’s name alongside Pythagoras serves as a reminder that the foundations of modern knowledge are deeper, older, and more interconnected than they may appear at first glance.