In a democracy, even death should not be delivered in the language of brutality.

There is a particular kind of silence that haunts the corridors of the Supreme Court of India—a silence born of centuries of precedent and the heavy weight of the law. But recently, that silence was broken by a question that should have been asked decades ago: Does a Republic, in the pursuit of justice, have the right to be a butcher?

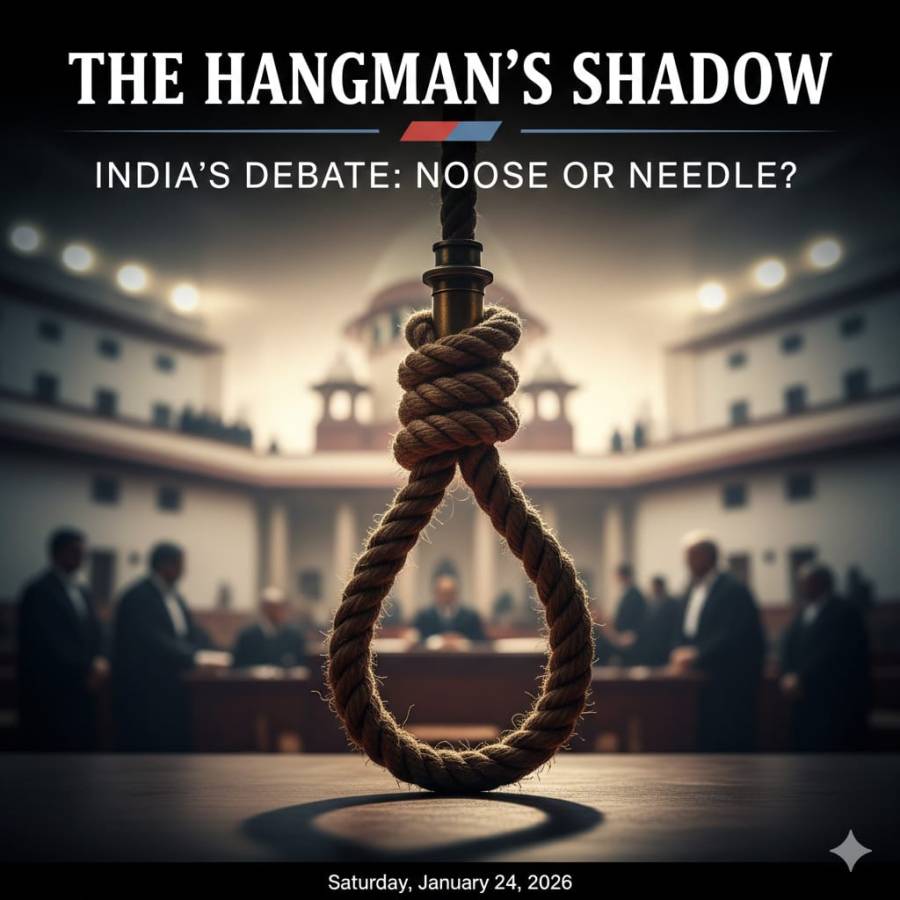

The debate is not over the guilt of the condemned, but over the dignity of their departure. For over a century, India has relied on the "long drop"—a piece of colonial theater involving a hemp rope, a wooden trapdoor, and a sudden, violent snap of the cervical vertebrae. Now, a Bench led by Justices Vikram Nath and Sandeep Mehta is peering into the dark of the execution chamber, asking if there is a way to end a life that doesn't feel like a relic of the Middle Ages.

The Bureaucracy of Retribution

The petition filed by advocate Rishi Malhotra isn't a plea for mercy; it is a demand for modernization. It suggests that if the State must kill, it should do so with the clinical, silent efficiency of a lethal injection or perhaps the sudden finality of a firing squad. The argument is rooted in the "right to die with dignity," a concept that seems like a legal oxymoron until you realize that even a man on the gallows remains a citizen of a constitutional democracy.

The Union government’s response, however, has been a study in grim pragmatism. They cling to the noose with the tenacity of a bureaucrat holding onto a filing cabinet. Their defense is that hanging is "safe and quick"—terms that sound jarringly domestic when applied to the business of death. They point to the botched horrors in the United States, where lethal injections have turned into hour-long agonies of collapsed veins and chemical burns. To the government, the rope is reliable. It works. It is, in their own terrifying lexicon, "civilized."

But the Court has sensed a rot in this logic. Justice Mehta’s stinging observation—that the government seems "unready to evolve"—cuts to the heart of the matter. It suggests an executive branch that finds comfort in the familiar, even when the familiar involves thirty minutes of strangulation.

Why the Common Man Must Care

To the man on the street, struggling with the rising cost of onions or the chaos of the commute, the mechanics of death row might seem like a distant, academic vanity. Why spend precious judicial time worrying about the comfort of a criminal who has committed the "rarest of rare" atrocities?

The answer lies in the mirror. When the State executes a man, it does so in your name. It is your hand on the lever; it is your collective morality that is tested. If we allow the State to kill with a method that is archaic and barbaric, we are admitting that our justice system is fueled not by the law, but by a primitive thirst for vengeance.

By questioning the "barbarity" of the gallows, the Supreme Court is actually building a shield for the common citizen. It reinforces a vital principle: the State’s power is not absolute. If the government is barred from being "cruel" to a murderer, it creates a standard of humaneness that protects everyone else—the protestor, the political dissenter, and the ordinary person in a police lockup. Every time we raise the floor for the treatment of the "least among us," we raise the standard of dignity for the entire nation.

The Myth of Deterrence

There is also the ghost of deterrence. The government quietly fears that if death becomes too "serene," it will lose its power to terrify. This is a revealing admission of a State that believes its authority is rooted in fear rather than the majesty of the law.

The Court has now demanded hard data. They want to know if science has found a way to kill without torture. This search for a "humane" way to kill is, of course, a pursuit of an oxymoron. There is no serenity in a state-sanctioned killing. But the very fact that we are having this conversation in 2026 is a sign of a maturing Republic.

As the Court prepares to deliberate on the written submissions, the shadow of the hangman is finally being measured against the light of the 21st century. Whether the rope is replaced by a needle or a gas chamber is almost secondary to the realization that the "how" of justice defines us just as much as the "why."

We are finally admitting that a civilization is judged not by how it treats its heroes, but by the restraint it shows toward its villains. The trapdoor is still there, but the air above it has finally begun to clear.

The government has raised concerns about the "botched" nature of lethal injections abroad.