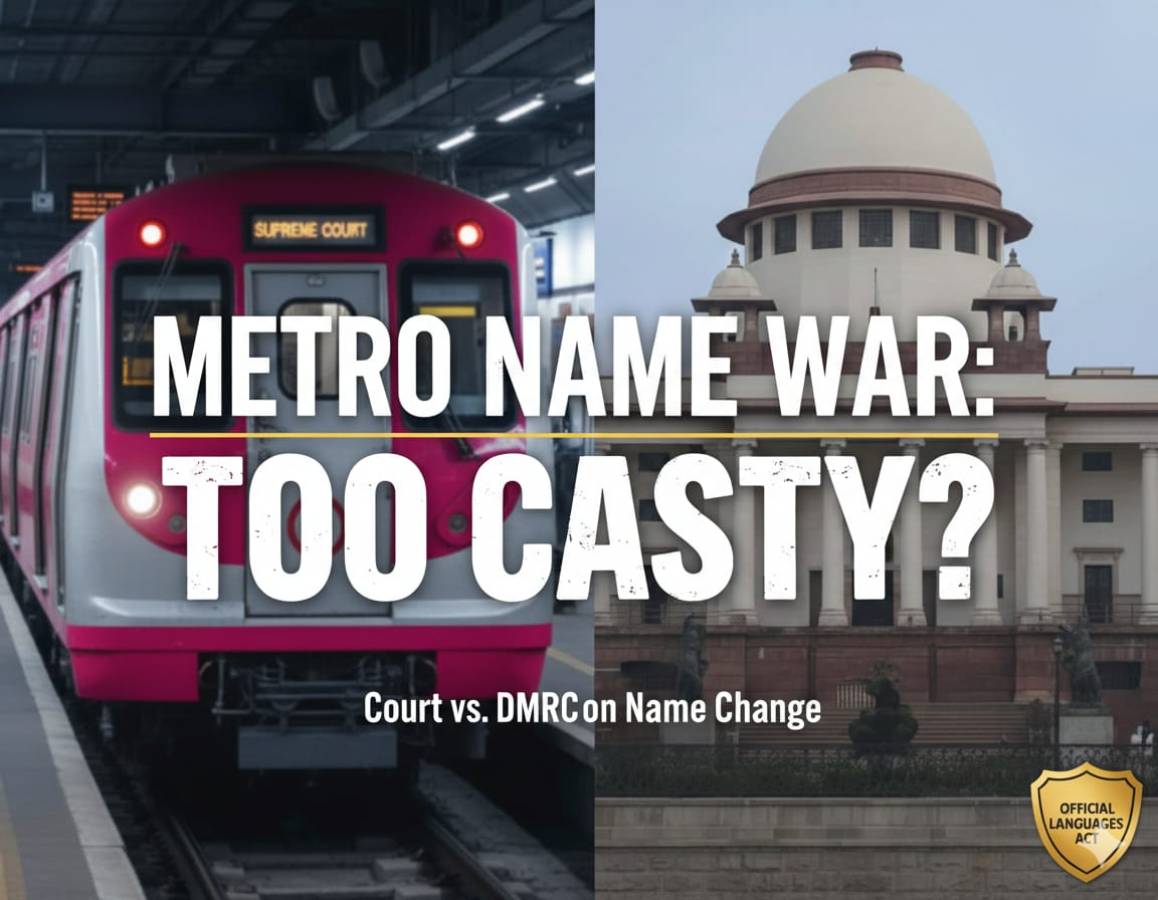

Can a name on a Metro signboard cost ₹45 lakh — and does the price of compliance outweigh the power of language? In Delhi, a battle over the words “Supreme Court” has turned into a larger debate about law, identity, and the true cost of honoring India’s Official Languages Act.

A seemingly simple question about translation has turned into a legal and administrative debate in the national capital. The Delhi Metro Rail Corporation (DMRC) has informed the Delhi High Court that it cannot change the Hindi name of the “Supreme Court” Metro station to “Sarvoch Nyayalaya,” arguing that the exercise would impose a significant financial burden.

The matter reached the court after advocate Umesh Sharma filed a plea contending that the existing naming format does not strictly follow official Hindi translation norms. According to the petitioner, public institutions must adhere to prescribed language rules, especially when it comes to signage and official communication. He argued that “Sarvoch Nyayalaya” is the appropriate Hindi equivalent of “Supreme Court” and should be reflected accordingly at the Metro station.

The Cost Concern: ₹40–45 Lakh

Responding to the plea, the DMRC maintained that altering the station’s Hindi name is not merely a cosmetic change. Its counsel submitted before the court that the estimated cost of implementing such a change would range between ₹40 lakh and ₹45 lakh.

The expenditure, the corporation explained, would cover multiple layers of modification, including:

- Replacing and reinstalling physical signboards at the station premises.

- Updating route maps displayed inside trains and at platforms.

- Revising digital displays across the Metro network.

- Making changes to official documents, printed materials, and system databases.

- Updating information on the Metro’s website and mobile applications.

According to the DMRC, the change would require coordination across various technical and operational departments. It would not only involve design and printing costs but also labor, installation, and system recalibration expenses.

Beyond financial implications, the corporation raised another concern: the possibility of opening the floodgates to similar demands. The DMRC cautioned that if the court directs a change in this case, it may trigger “multiple litigations,” with individuals or groups approaching courts to seek name alterations at other stations. This, it argued, could create a chain reaction, adding to administrative complexity and financial strain.

The Court’s Stand: Law Over Logistics

The Delhi High Court, however, appeared unconvinced by the cost-based argument. During the hearing, the bench observed that the fear of further litigation cannot serve as a justification for ignoring statutory obligations.

“Multiple litigation is not the defence. We have to honour the act,” the court remarked, underlining that compliance with the law takes precedence over administrative inconvenience.

The bench referred to the Official Languages Act and the accompanying Rules of 1976. These provisions mandate the use of Hindi in the Devanagari script for official purposes of the Union, alongside English. The court pointed out that:

- Hindi must be written in Devanagari script.

- Signboards, manuals, and official nameplates must display both Hindi and English.

- Even official stationery, letterheads, and printed materials are required to follow bilingual norms.

The judges emphasized that statutory requirements cannot be bypassed solely on the ground of financial inconvenience. If the law requires certain standards to be met, public authorities are duty-bound to comply.

Language, Identity, and Administration

While the immediate issue concerns a single Metro station, the case touches on a broader and sensitive subject: language policy in India. The balance between Hindi and English in public administration has long been debated. For many, adherence to official language rules represents respect for constitutional provisions and linguistic identity. For others, practical considerations such as cost, uniformity, and clarity for commuters take priority.

In a city like Delhi, where millions rely on the Metro daily, signage plays a critical role in navigation. The DMRC has built a reputation for efficiency and standardized communication. Any alteration, even in terminology, requires careful implementation to avoid confusion.

What Happens Next?

The High Court has directed both the Central Government and the DMRC to file detailed affidavits explaining their positions. The court has made it clear that the mandate of the Official Languages Act must be examined seriously, irrespective of the projected financial burden.

The final outcome could have implications beyond the “Supreme Court” station. If the court rules in favor of strict compliance, other public bodies may also need to reassess how they implement bilingual naming conventions.

For now, the debate continues — not merely about a name on a signboard, but about the intersection of law, language, and public expenditure in India’s capital.