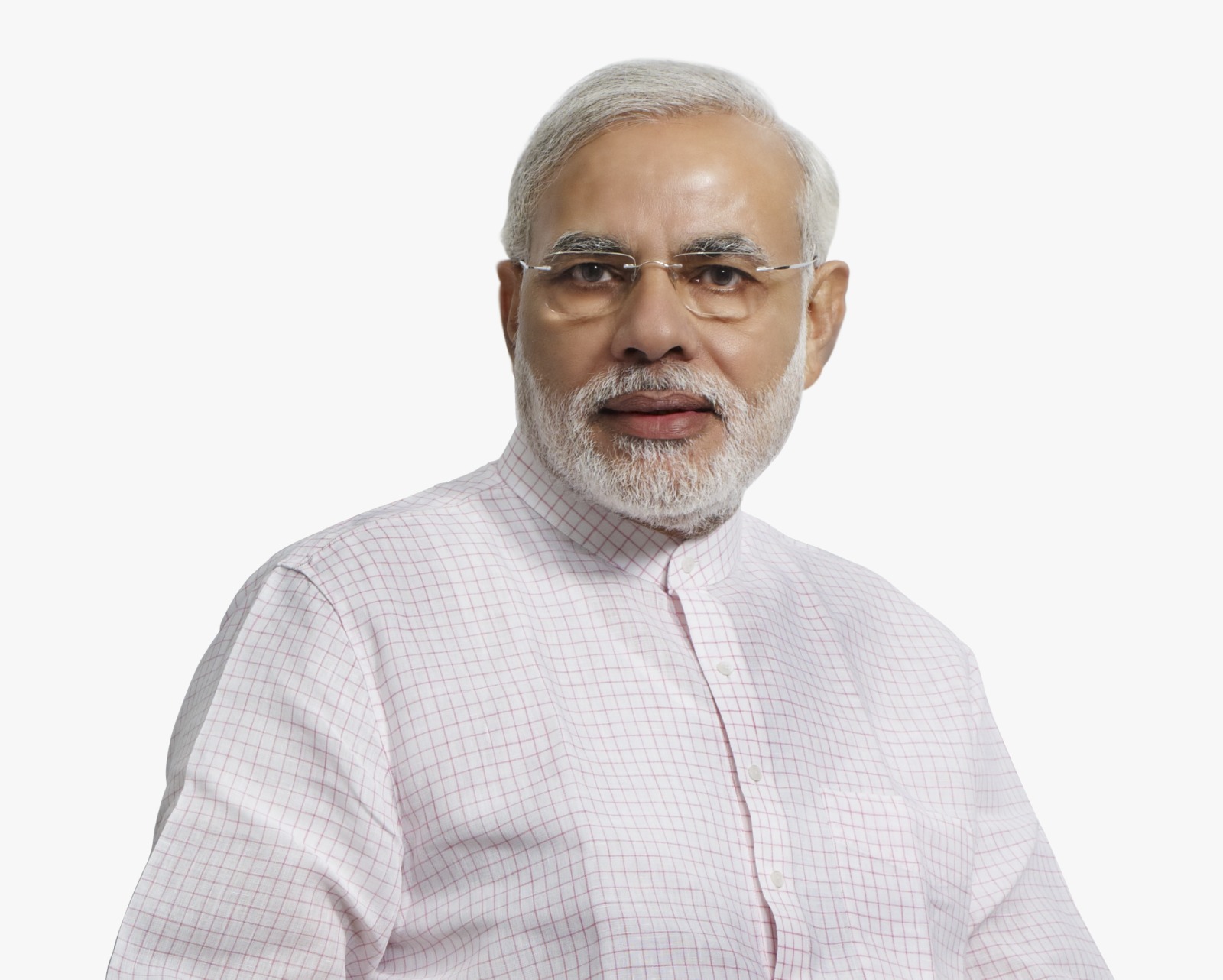

In a democracy, the relationship between the ruler and the chroniclers of public life has always been a dance of necessity and suspicion. Leaders need the press for legitimacy, while the press needs leaders for relevance. Yet India finds itself at an unusual moment. The current Prime Minister has consistently chosen to avoid direct engagement with the mainstream media in the form of press conferences or studio debates. Unlike his predecessors and other premiers across the world, he does not subject himself to unscripted questions. Still, the mainstream media covers him with an admiration that often borders on reverence.

To understand this paradox, one must turn to the old masters of political thought. Aristotle wrote that politics is not only about ruling but also about being seen to rule. Visibility, he argued, was the foundation of authority. Centuries later, Machiavelli sharpened this idea in The Prince. A ruler, he advised, need not always be loved or even understood. It is enough if he is perceived as powerful, decisive, and ordained by fortune. In this sense, India’s Prime Minister has mastered the optics of rule without relying on the traditional arena of media interrogation.

The Stage Without the Interlocutor

It would be unfair to say that the Prime Minister avoids the public eye. On the contrary, he is one of the most visible leaders India has ever had. He addresses mass rallies across the country, participates actively in Parliament, leads delegations abroad, and regularly speaks on global platforms. His presence dominates both national and international stages. Yet, what sets him apart is his refusal to engage in unscripted exchanges with journalists. He does not sit for open press conferences, nor does he appear in news studios to take questions, as leaders in many democracies routinely do.

In the past, press conferences acted as a stage where leaders displayed their wit, intellect, and accountability. Nehru sparred with journalists to showcase his vision, Indira Gandhi endured tough questions as a test of her authority, and Vajpayee used press interactions to display oratory charm. The current Prime Minister has inverted this expectation. Instead of answering questions, he has built a communication structure where he alone sets the terms. From radio addresses like Mann ki Baat to carefully curated social media messages, he reaches the public directly, without the filter of press scrutiny.

Paradoxically, this absence of dialogue has not created hostility in mainstream media. On the contrary, most outlets continue to treat his speeches, silences, and even gestures as matters of national importance. His refusal to engage is interpreted as strategic mystique rather than evasion. The media, rather than protesting, often amplifies his voice.

The Prince and the Image

Machiavelli argued that rulers must control appearances, for people “judge more by the eye than by the hand.” The Prime Minister embodies this maxim. His image—whether meditating in a cave before elections or standing tall during foreign visits—becomes news in itself. Mainstream media channels devote hours to analyzing his attire, his body language, and his silences. In this theatre of politics, the Prime Minister plays both the actor and the director, while the media willingly becomes the stagehand.

The question arises: why does the media, whose traditional role is to question authority, not rebel against this arrangement? Part of the answer lies in the changed economics of journalism. Ratings, advertising, and the hunger for sensational content have pushed many outlets into a symbiotic relationship with political power. To criticize the absence of press conferences might mean losing access to official narratives, while praise ensures a steady stream of stories. The marketplace of news rewards loyalty to spectacle over loyalty to truth.

Aristotle’s Warning

Yet Aristotle would caution against confusing spectacle with stability. For him, politics was the art of ensuring the good life for citizens, not merely the consolidation of authority. A polity without critical dialogue risks mistaking popularity for virtue. When rulers are treated as demigods, the public sphere weakens. Citizens may cheer their leader, but they lose the habit of questioning him. The Prime Minister’s success in bypassing mainstream media is therefore not just a personal triumph; it reflects a deeper transformation of democratic culture in India.

The Silent Contract

What emerges is an unspoken contract between the leader and the press. The Prime Minister offers the media a steady flow of images, slogans, and orchestrated events. In return, the media grants him the aura of inevitability. This contract mirrors the logic of The Prince. Machiavelli advised rulers to avoid situations where their weaknesses could be exposed. By never facing open questions, the Prime Minister eliminates the risk of unpredictability. The media, instead of lamenting the loss of accountability, treats this control as charisma.

Implications for the Future

This relationship raises troubling questions for the health of democracy. If mainstream media normalizes the absence of dialogue, the space for dissent shrinks. Alternative media and independent voices may try to fill the gap, but their reach is often limited compared to the vast machinery of established outlets. Citizens are left with narratives shaped more by power than by inquiry.

Still, one cannot deny the brilliance of the strategy. The Prime Minister has achieved what Machiavelli would admire: the ability to dominate public imagination without exposing himself to risk. He has shown that in the age of digital communication, leaders can bypass traditional gatekeepers and still command unwavering coverage. In this sense, he is both a product of history and an innovator of its future.

Final Take

The tale of India’s first Prime Minister who never truly engages with mainstream media through open press conferences yet receives their devotion will be remembered as a turning point in the relationship between power and press. It demonstrates how old ideas from Aristotle and Machiavelli still echo in modern politics. The ruler controls visibility, the press amplifies it, and the public consumes it. The cost, however, is the erosion of questioning, which lies at the heart of democratic life.