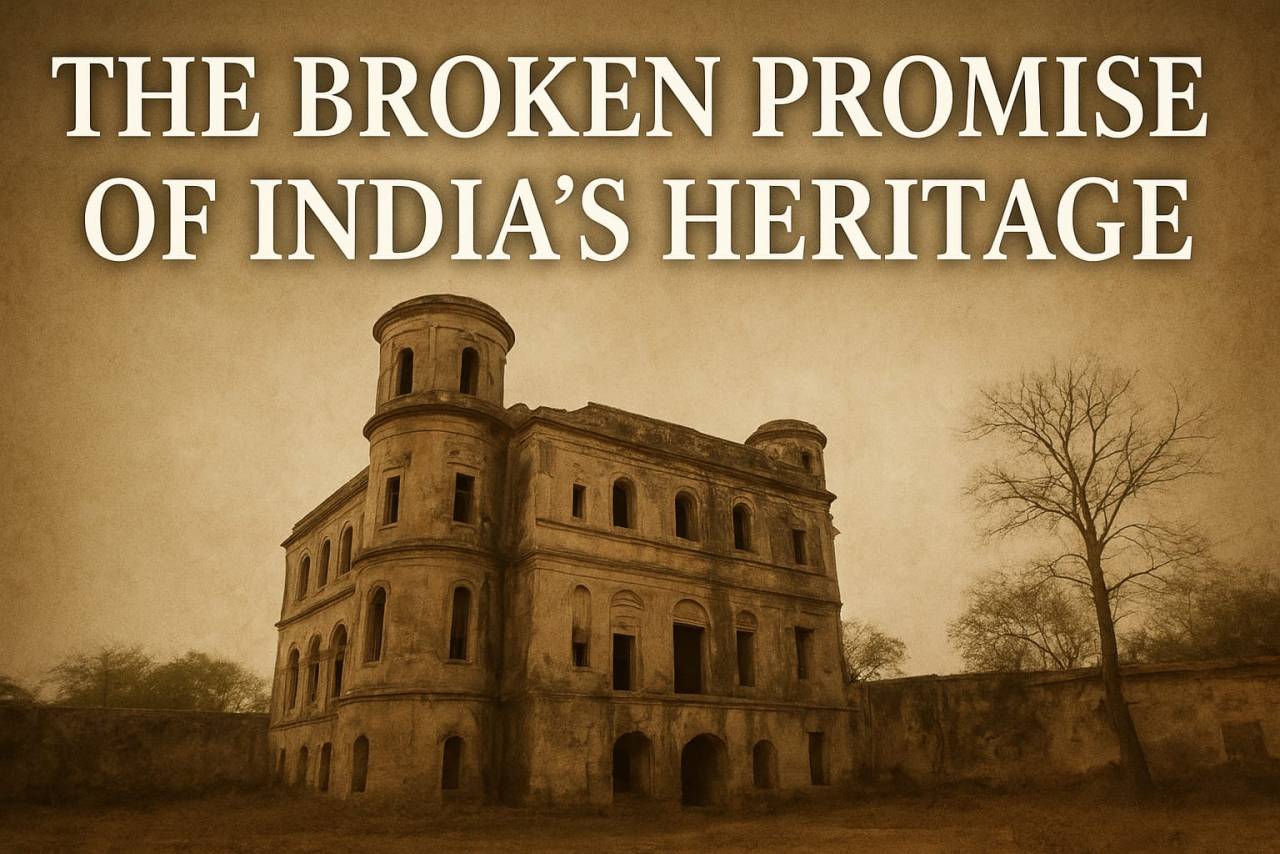

India’s architectural landscape tells the story of millennia — a story of civilizations, empires, and communities that left their mark through timeless structures. From the majestic forts of Rajasthan to the colonial-era mansions of Lucknow, every brick speaks of a glorious past. Yet, in the 21st century, this legacy is under threat. As modernization races ahead, the very monuments that define India’s historical identity are crumbling, neglected, or repurposed beyond recognition. The country’s promise to protect its heritage remains unfulfilled, exposing deep flaws in conservation policy, bureaucratic will, and public awareness.

The Fading Echoes of History

India boasts thousands of heritage structures — ancient temples, palaces, colonial bungalows, and civic buildings — that reflect its cultural diversity and historical evolution. But a large number of these are now deteriorating at alarming rates. Many are caught between ownership disputes, urban expansion, and commercial interests. Even in cities like Lucknow, Kolkata, and Puducherry, which once stood as models of cultural preservation, heritage buildings are being demolished, encroached upon, or carelessly altered.

One striking example is the Butler Palace in Lucknow, a grand symbol of colonial-era architecture once admired for its elegance and historical importance. Once a residence for British officials and later used for government purposes, the structure now lies in neglect. Plans to repurpose it into a modern facility have drawn criticism from conservationists who argue that adaptive reuse must not come at the cost of erasing historical authenticity. The palace, with its fading walls and silent corridors, mirrors the fate of countless other monuments across the country — forgotten until it’s too late.

Commercialization vs. Conservation

A worrying trend in recent years is the transformation of heritage spaces into commercial ventures. Many old buildings, unable to sustain themselves under government control, are leased to private developers or turned into hotels, cafes, or offices. While adaptive reuse can sometimes breathe new life into a monument, it often prioritizes profit over preservation.

For instance, the Charnock Mansion in Kolkata, a colonial-era structure named after the city’s founder, has been partially converted for commercial use. Its façade still retains hints of British architecture, but its interiors have undergone drastic changes. Similarly, Roxy Cinema, once an art deco landmark in Kolkata, has been left abandoned after years of indecision over its fate. Such neglect highlights the absence of a coherent national policy that balances heritage preservation with modernization.

The argument for private involvement is often based on financial limitations. Government agencies like the Archaeological Survey of India (ASI) are overstretched and underfunded, responsible for over 3,000 protected monuments but lacking sufficient manpower and modern conservation tools. However, the alternative — allowing private companies to manage heritage sites — risks commercialization without proper accountability.

Lessons from Puducherry: A Model in Decline

The French Quarter in Puducherry once stood as a shining example of successful heritage management. Its pastel-colored villas and cobbled streets attracted visitors from across the world, offering a glimpse into the town’s colonial past. However, over the last decade, rapid urbanization, real estate development, and lax enforcement of conservation laws have altered its landscape.

One of the most iconic structures, Calve College, established in the 19th century, has seen repeated restoration efforts but still faces threats from neglect and encroachment. Conservationists point out that local authorities have failed to create a sustainable plan to preserve such institutions while adapting them for modern use. Puducherry’s example reveals how even well-maintained heritage zones can deteriorate without consistent policies, funding, and community participation.

Policy Gaps

Despite India’s long history of conservation, the system remains fragmented. The Ancient Monuments and Archaeological Sites and Remains Act (1958) protects centrally recognized monuments, but thousands of heritage buildings under state or municipal control lack proper classification or legal protection.

Projects such as the HRIDAY (Heritage City Development and Augmentation Yojana) and Smart Cities Mission were launched with the promise of integrating heritage with urban planning. However, implementation has often been slow and inconsistent. Many initiatives focus more on beautification — repainting façades, installing lights, or building walkways — rather than on the structural restoration and preventive maintenance that heritage buildings require.

Adding to this is the absence of trained heritage professionals at the local level. Most municipalities treat conservation as an aesthetic task rather than a technical discipline requiring experts in architecture, archaeology, and environmental planning.

Community and Cultural Responsibility

Preserving heritage is not just the government’s duty — it’s a collective responsibility. Local communities are often the first to witness the decay of heritage structures, yet they are rarely involved in the decision-making process. Encouraging citizen participation, creating awareness programs, and integrating heritage education into school curriculums can help develop a sense of ownership and pride.

In many successful global examples, such as in Europe and Japan, heritage conservation is a community effort. India can learn from these models by creating local heritage trusts and offering tax incentives to property owners who preserve historical buildings.

Rebuilding the Promise

India’s identity as a nation is deeply intertwined with its built heritage. Each fort, palace, and public building is a chapter in the country’s story — from Mughal artistry to British engineering and indigenous craftsmanship. Losing these structures means erasing parts of that story forever.

A sustainable future for India’s heritage demands stronger legal frameworks, better funding, and professional management. Digital documentation, 3D mapping, and public-private partnerships with strict guidelines can ensure both preservation and usability. Above all, a cultural shift is needed — from viewing old buildings as outdated relics to recognizing them as living embodiments of national memory.

Final Take

As India strides toward becoming a modern economic power, it must not leave behind the monuments that narrate its journey. The broken promise of heritage conservation can still be mended — but only through respect, responsibility, and vision. The grandeur of Butler Palace, the legacy of Roxy Cinema, and the charm of Calve College deserve more than to fade into history books. They deserve a second life — one that honors their past while embracing the future.

zlZPydyflWscybesE

3 months agotwQRCMDTCEsuxBHaS

mnGwdiwGJAEzXNly

3 months agooIEGvHiRTlmdLsaC