The question of who will be the next Dalai Lama has become more than a religious concern — it now represents a power struggle between centuries-old Tibetan tradition and modern Chinese political authority. With the 14th Dalai Lama nearing his 90th birthday, China has stated that it will not accept any successor chosen by Tibetan monks unless it receives the government’s official approval. This declaration has stirred concern across Southeast Asia, where Tibetan Buddhism remains deeply rooted in both culture and conscience.

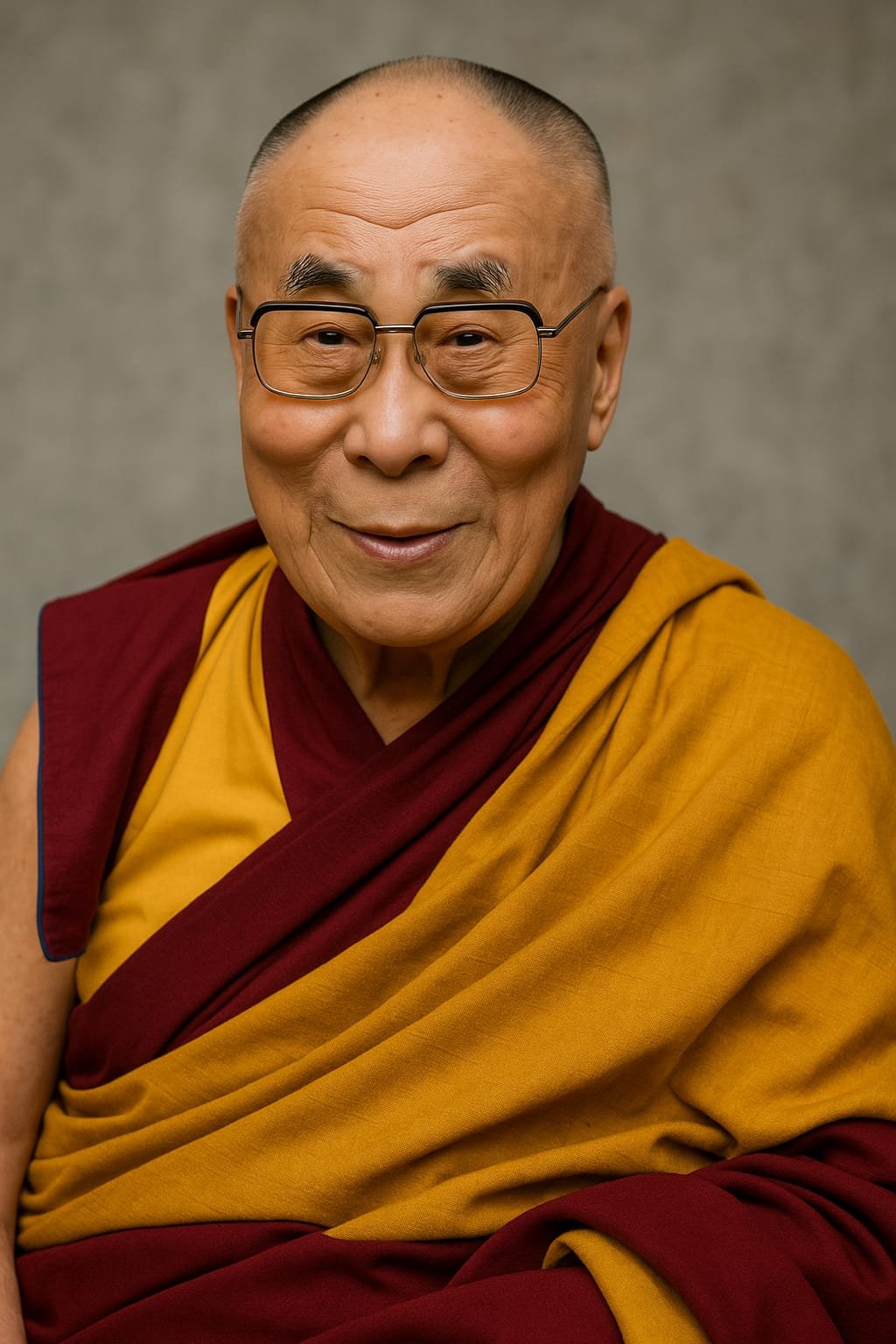

Tibetan Buddhists believe the Dalai Lama is the reincarnation of Avalokiteshvara, the bodhisattva of compassion. Each new Dalai Lama is selected through sacred signs, visions, and spiritual recognition by senior monks. The current Dalai Lama, Tenzin Gyatso, was identified at the age of two after a series of traditional tests and was formally recognized as the spiritual leader of Tibet.

However, China has rejected that process and insists that all high reincarnations, including the next Dalai Lama, must be chosen through the “Golden Urn” system—a Qing dynasty method that draws lots from a ceremonial urn—and must be approved by the Chinese Communist Party. This claim is part of a larger pattern by Beijing to control religious and cultural institutions in Tibet, which it has ruled since the 1950s.

The Dalai Lama, who fled to India in 1959 following China’s military crackdown in Tibet, has strongly opposed Beijing’s interference in spiritual matters. In 2015, he created the Gaden Phodrang Trust to manage the process of identifying his successor, making it clear that any legitimate reincarnation would not come from a region under political pressure. “Rebirth is a spiritual matter,” he has said repeatedly. “No government can decide it.”

This situation brings to mind the troubling disappearance of Gedhun Choekyi Nyima, the boy the Dalai Lama identified in 1995 as the 11th Panchen Lama. Within days of the announcement, the six-year-old boy and his family vanished. They have not been seen in public since. China then appointed its own Panchen Lama, who was approved by state agencies. Yet, many Tibetan Buddhists around the world still recognize the Dalai Lama’s original choice, believing that China’s version lacks spiritual legitimacy.

Southeast Asia watches these developments with growing concern. Countries such as Nepal, Bhutan, and regions of India have deep religious ties with Tibetan Buddhism. Monks, students, and believers in these areas look to the Dalai Lama not just as a religious leader but as a teacher and symbol of ethical resistance. His messages of compassion and nonviolence are studied in monasteries, taught in schools, and shared widely in spiritual communities.

India, in particular, holds a central place in this unfolding story. The Dalai Lama has lived in Dharamshala for more than six decades, where the Tibetan government-in-exile is based. While India officially acknowledges Tibet as a part of China, it continues to provide a safe haven for Tibetan exiles and permits religious freedom among them. This careful balancing act often leads to friction with Beijing, especially during sensitive moments like succession discussions.

The fear among many followers is that Beijing will install its own Dalai Lama—one who is loyal to the state rather than to the teachings of the tradition. If that happens, the world could face a confusing scenario with two rival Dalai Lamas: one recognized by the Chinese government and another by the Tibetan community in exile. The result could fracture Tibetan Buddhism and weaken its global unity.

For millions of Buddhists across Southeast Asia and beyond, the next Dalai Lama should emerge through sacred rituals, not political appointments. The core question—Who will choose the next Dalai Lama: monks or Beijing?—reflects not only a religious dilemma but a broader issue of identity, freedom, and cultural survival.

In a region where belief often flows deeper than borders, many are hoping that faith, not force, will guide the future.