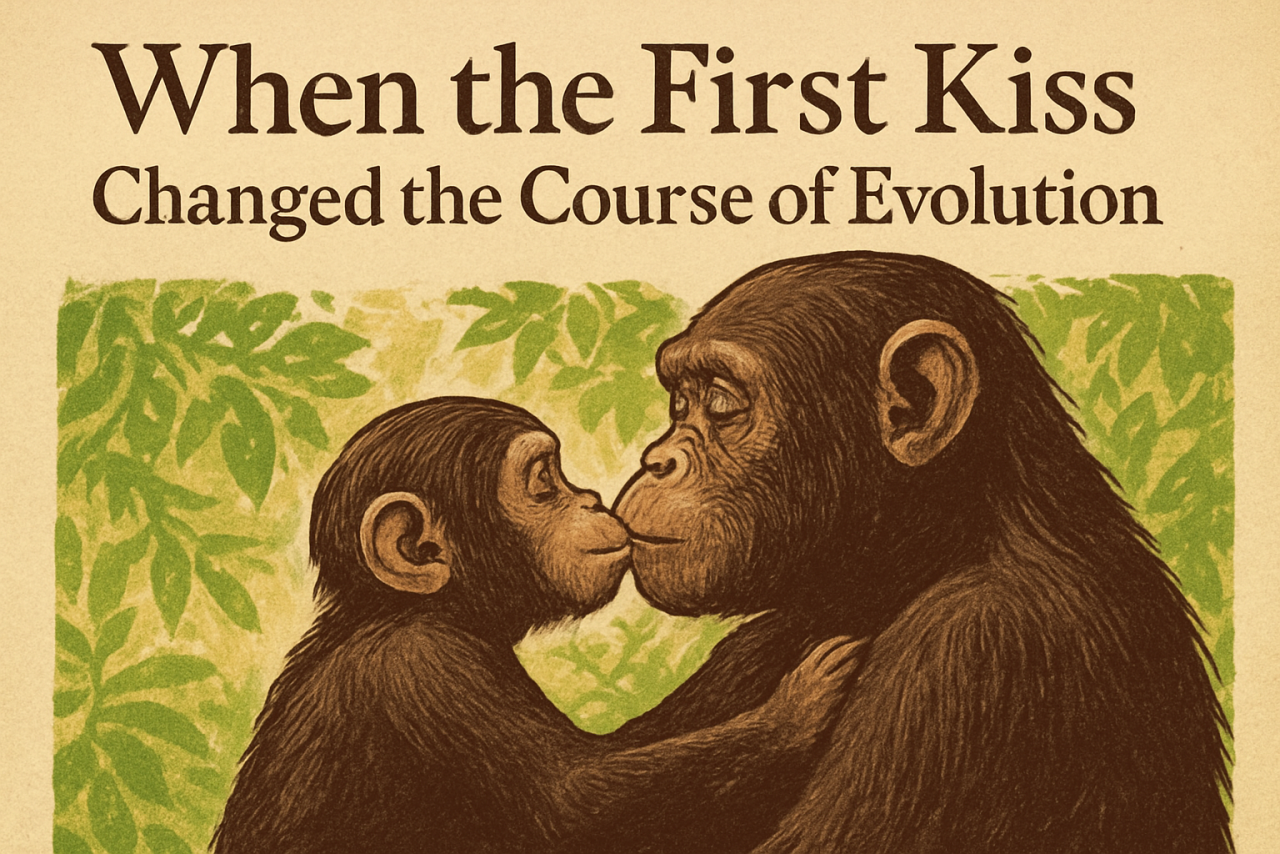

Long before humans learned to whisper affection or etch love into poetry, an ancient gesture quietly began shaping the emotional architecture of primates. According to a new study by researchers from Oxford University and the Florida Institute of Technology, the origins of kissing trace back not to early humans, but to the ancestors of great apes—nearly 20 million years ago.

It is a discovery that reframes one of our most intimate behaviours. Kissing, the researchers argue, did not suddenly appear as some romantic leap in human evolution. Instead, it was likely inherited from a shared primate ancestor, passed through generations of chimpanzees, bonobos, gorillas, orangutans—and eventually, us.

A Gesture Older Than Humanity

The research team combined primate behavioural observations with evolutionary modelling to pinpoint when this early form of mouth-to-mouth contact emerged. Their models repeatedly pointed to a window between 21.5 and 16.9 million years ago—long before Homo sapiens ever walked the Earth.

But this “first kiss” wasn’t the tender, poetic version humans often imagine. The study describes it in more functional terms: a non-aggressive mouth-to-mouth interaction that didn’t necessarily involve food sharing. And yet, despite seeming biologically risky—after all, it could spread microbes—this behaviour persisted. That itself was a clue.

Why Did Early Primates Kiss?

The researchers suggest that kissing may have played a role in strengthening social bonds long before love stories and romantic traditions gave it new meaning. Among present-day primates, similar gestures appear in several contexts:

- Mothers soothing infants

- Individuals reinforcing alliances

- Companions offering reassurance or reconciliation

These patterns hint that the behaviour initially evolved as a social tool rather than a romantic one. Platonic pecks, researchers note, could have helped primates navigate the complexity of group living—an evolutionary advantage that may have outweighed the risks.

An Intimate Thread Through Evolution

Modern evidence reinforces the idea that kissing served biological functions beyond affection. For instance, Neanderthals are believed to have shared microbes and exchanged saliva with their partners—a sign of familiarity and bonding—well after splitting from the human lineage hundreds of thousands of years ago.

Even today, the simplest kiss can trigger hormonal cascades that foster trust, calmness, and connection. The researchers suggest these biochemical rewards may be remnants of the same evolutionary pathways that encouraged ancient primates to engage in early forms of the gesture.

Beyond Romance, a Universal Language

The image of a baby chimpanzee gently pressing its mouth against its mother’s—a behaviour observed across zoos, sanctuaries, and wild habitats—captures the essence of what the study proposes: kissing, in its many forms, has always been about connection.

Whether it appears as a mother’s reassurance, a greeting between familiar companions, or the spark between partners, the gesture is woven into primate history. Its deep evolutionary roots help explain why it remains so instinctive, so universal, and so enduring.

A Gesture Carried Across Millennia

This study doesn’t just add a fascinating footnote to the story of human affection—it deepens our understanding of how behaviours evolve, survive, and shape species over time.

The next time two humans share a kiss, they might be participating in a ritual older than humanity itself—an echo of an ancient world where early primates first discovered the power of a simple touch between mouths.