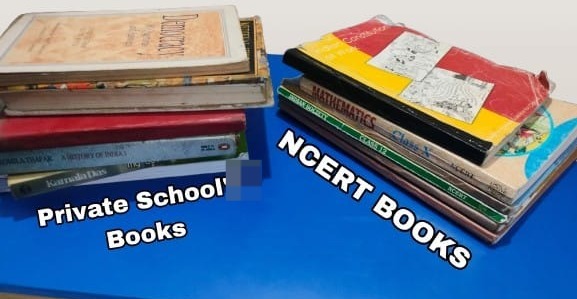

India takes pride in calling education a fundamental right, yet the everyday reality of schoolbooks reveals a different story. In government schools, children study from prescribed NCERT or state board books, priced low and often distributed free. Across the street, private school children are handed long booklists filled with glossy volumes from commercial publishers. Parents must buy these at staggering prices, sometimes two to five times the cost of government books. The difference is not merely one of quality or choice. It is a policy failure that allows education to be commercialized while the government looks away.

At the root lies a glaring question: if the government can produce and distribute affordable textbooks for millions of students in government schools, why not extend the same to private schools? Why should two children studying the same syllabus under the same board use two different sets of books—one accessible, the other exploitative? The absence of a universal policy for textbooks is the gap where private schools and publishers thrive, creating a parallel market that preys on parental anxieties about quality and competitive edge.

The government’s silence is not accidental. Textbook publishing is a lucrative industry, and private schools form its captive market. Publishers aggressively market to school administrations, promising updated content, attractive layouts, and extra practice material. In return, schools add these books to mandatory lists, leaving parents with no alternative. Without regulation, this cycle turns education into a profitable business at the expense of family budgets.

For parents, the impact is severe. Government books often cost less than ₹100 per subject, but private school lists can run into several thousand rupees per child each year. Families with two or three school-going children spend amounts that rival annual household essentials. The financial stress is visible across cities and small towns, where middle-class and lower-income families stretch budgets, take loans, or cut back on other needs to meet inflated educational costs.

The larger tragedy is that this system cements inequality. Government schools, already struggling with infrastructure and quality of teaching, are left behind in perception because their books are seen as inferior. Private schools exploit this perception to justify costly alternatives. Yet in truth, NCERT books are globally acknowledged for their clarity and rigor, often considered better for national exams like UPSC and JEE. The irony is sharp—students in government schools use the same books that define India’s toughest exams, while private school students are trapped in glossy but overpriced substitutes.

The fault lies squarely with government policy. By failing to impose universal textbooks across schools, authorities have surrendered the education market to profiteering. If the state had mandated NCERT or state board books for all schools, both government and private, the textbook industry would have lost its monopoly over anxious parents. Uniformity would have not only reduced costs but also ensured equality in learning standards.

Instead, we see a fragmented system: one set of affordable books for government schools, another costly set for private schools. This divide encourages the notion that private education is inherently better, not because of superior pedagogy but because of expensive packaging. It also deepens the class divide in education, where a child’s future appears tied not to talent but to a parent’s purchasing power.

The solution is neither radical nor impossible. The government already has the infrastructure to produce and distribute NCERT and state board books nationwide. Extending this policy to private schools requires political will and regulatory clarity. Schools can be allowed to use supplementary material, but the core textbooks should remain the same across the country. This would not only lower costs but also level the playing field for students, making board examinations and competitive tests fairer.

Until then, the “loot” will continue. Parents will bleed money year after year, publishers will profit, and private schools will reinforce their image as exclusive domains. What should have been a right is reduced to a privilege, and what should have been uniform is turned into a business model.