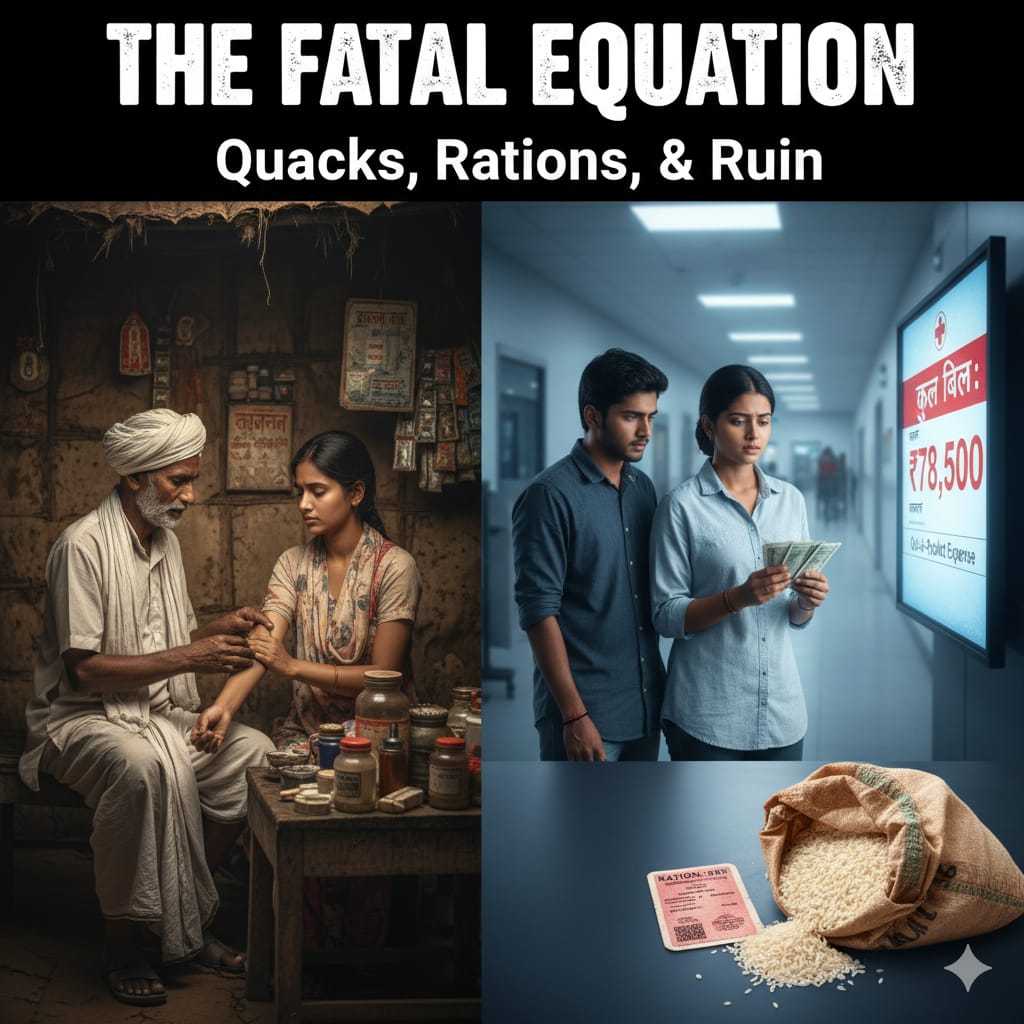

For over 80 crore people in India, more than the population of Europe, life balances precariously on two government lifelines: 10 kilograms of subsidized food grains and the promise of public health. When either system falters, the rural poor face a deadly choice: rely on unqualified local healers or risk financial ruin in the private healthcare market. This is the fatal equation that defines medical access across much of rural India.

The Survival Margin: Why Food Subsidies Define Health Choices

The widely reported statistic that 80 crore people depend on subsidized rations speaks to a fundamental economic vulnerability. For these families, the food subsidy is not a luxury but a critical margin of survival. By stabilizing the largest household expense like feeding the family—it frees up a minimal amount of cash for all other needs, including healthcare.

This tiny cash reserve dictates every medical decision. When a child falls ill, the family’s priority is immediate but low-cost access. They cannot afford to let a fever eat a day’s wages.

This is where the local, unqualified practitioner, often derogatorily called a 'quack', steps in. He is accessible 24/7, lives down the road, charges a mere ₹50 for a consultation, and critically, may offer medicine on credit. For a family whose entire financial planning revolves around the subsidized ration, this immediate, cheap, and flexible option is simply unbeatable. The local healer, though dangerous, is the default primary care provider because the formal system is either too distant, too under-resourced, or too expensive.

The Systemic Failure that Empowers the Unqualified

The overwhelming reliance on informal health providers, which some surveys suggest is responsible for up to 70% of rural primary care. It is a clear indictment of the formal healthcare infrastructure.

Inaccessibility: Qualified doctors gravitate toward urban centres for better pay and facilities. As a result, many villages lack a functioning Primary Health Centre (PHC) or have one that is severely understaffed and poorly stocked.

Time and Cost: Traveling to a distant, formal public facility takes a full day, costs money in transport, and often ends with a long wait only to find the necessary tests or medicines are unavailable.

The local healer fills this vacuum effectively. Though his treatment often involves the misuse of potent antibiotics and steroids, providing quick but unsustainable relief, the perception of efficacy is strong. This trust, built on instant access, tragically outweighs the risks of incorrect diagnosis and delayed referral.

The Annihilation of Debt: The Private Sector Predation

When a serious illness strikes such as a snakebite, a complicated infection, or a necessary surgery, the family has no choice but to seek care at a formal hospital, usually in the private sector. This is the point where the meagre financial stability provided by the food subsidy is instantly vaporized.

India’s public spending on health is low, leading to some of the highest Out-of-Pocket Expenditure (OOPE) rates in the world. For the rural poor, this means paying virtually all hospital costs directly.

The private hospital bill, inflated by expensive diagnostics, branded drugs, and procedure fees, often amounts to the family's annual income or more. The money saved by the subsidized 10kg of grain becomes irrelevant against a ₹50,000 bill. The only recourse is to borrow at high interest or sell productive assets like land or livestock.

This pattern is quite obvious in rural India. The catastrophic health expenditure is a major factor pushing millions of rural households into poverty every year. The irony is bitter and harsh. The government keeps the poor from starving with a ration card, but the formal healthcare sector ensures they are financially ruined the moment they fall ill.

To break this vicious cycle, the government must prioritize massive, effective investment in accessible public health facilities, making qualified care affordable and proximate. Until that happens, the 'quack' will remain a necessity and the private hospital a looming spectre of debt for those who already live at the sharp edge of poverty.