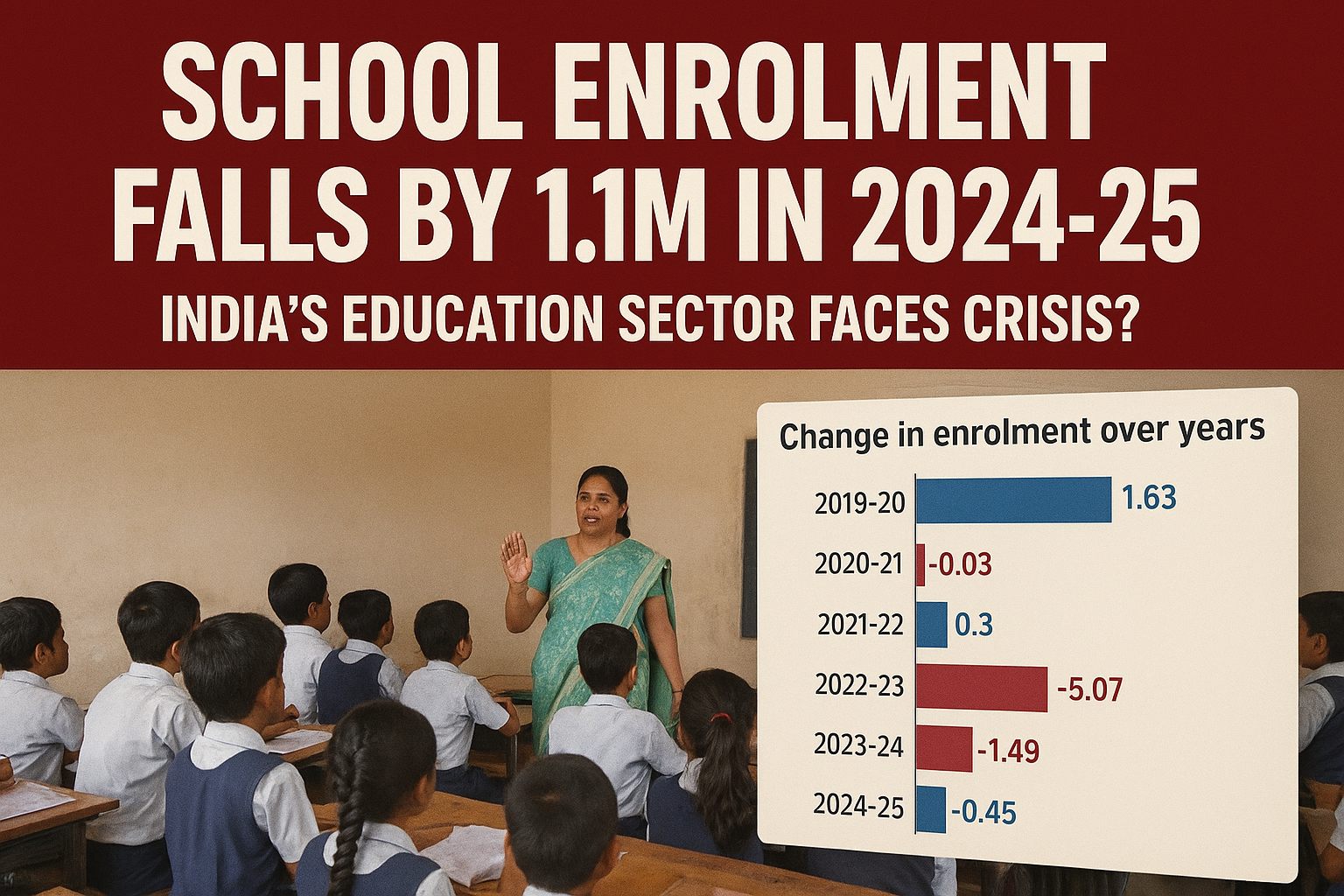

The Government of India speaks often of its ambition to make the country a Vishwaguru, a teacher to the world. Yet the latest enrolment figures from schools paint a very different picture. According to government data, enrolment across Indian schools fell by 1.1 million students in 2024-25. This is not a minor statistical change but a signal of deeper troubles in the education system. The sharpest decline has been recorded in the early years of schooling, which forms the foundation of a child’s learning journey.

Total enrolment slipped by 0.45 percent from 248 million in 2023-24 to 246.9 million in 2024-25. Within this, the foundational stage from pre-primary to Class 2 lost nearly 2.5 million students. In contrast, some higher classes showed small gains. These numbers underline that Indian families are either delaying school admission for young children or withdrawing them altogether. For a country that aims to showcase its intellectual strength to the world, such signals cannot be ignored.

Demographic Changes and Beyond

Officials attribute part of the decline to demographic shifts. India’s fertility rate has fallen steadily, from 2.8 in 2006 to 2.0 in 2022. Fewer children being born will naturally reduce enrolment numbers. However, this explanation is incomplete. Declines are sharper in some states than others, and migration has also played a role. Families from marginalised backgrounds often move to cities for work. Their children either drop out or fail to find places in new schools. The issue is not just fewer births but also weak systems to absorb displaced and vulnerable children.

The fall in pre-primary enrolment in 2020-21 was linked to the Covid-19 pandemic and lockdowns, as many parents avoided sending children to school. But by 2024-25, the pandemic excuse has worn thin. What remains is an education system unable to retain its youngest learners in meaningful numbers.

Private Schools on the Rise

The same data shows a continuing shift toward private education. Enrolment in private schools rose from 90 million to 95.8 million, while government schools declined from 127.4 million to 121.5 million. Parents who can afford fees are increasingly abandoning government schools, which are supposed to be the backbone of education for the majority. The migration is driven by perception. Parents believe private schools provide better teaching and discipline, even if the actual learning outcomes are often questionable. This steady erosion of trust in public education undermines the state’s claim to universal and quality schooling.

Unequal Impact on Marginalised Groups

The enrolment crisis has not been uniform. Scheduled Caste students recorded the largest fall, losing over 810,000 enrolments. Other Backward Classes lost around 370,000, and Scheduled Tribes nearly 250,000. Even the Muslim community saw a fall of 138,000 students. These numbers tell us that education remains most fragile for communities already facing economic and social disadvantages. The promise of equal opportunity through schooling is slipping away for millions.

When marginalised children drop out or fail to be admitted, the dream of an inclusive knowledge society breaks down. India cannot claim to be marching toward global leadership while failing to keep its most vulnerable inside classrooms.

Gender Picture

There is at least one positive sign. Girls’ enrolment rose by 32,925 in 2024-25. Girls now represent 48.3 percent of the total student population, up from 48.1 percent a year earlier. However, this improvement looks modest against the backdrop of 1.15 million fewer boys. The rise in girls’ numbers may partly reflect targeted schemes and a growing social push to educate daughters. Still, when overall enrolment is shrinking, even this achievement risks being overshadowed.

Access and Quality Remain Stagnant

Gross Enrolment Ratios reveal the hollowness of progress. The foundational stage stagnated at 41.4 percent, while coverage in the secondary stage declined from 56.5 percent to 55.8 percent. Middle stage enrolment, however, improved from 89.5 percent to 90.5 percent. These mixed figures show that while some older children are being retained, the youngest remain at risk of exclusion. Once the next census data is released, many of these numbers will be revised, but the broad trend of uneven access is unlikely to change.

Infrastructure has seen modest improvement. Among the 1.47 million schools, 98.6 percent now have drinking water facilities, and 98.8 percent have toilets. Yet only 54.7 percent have computers, and less than half have internet access. Without digital connectivity, the talk of preparing students for a modern knowledge economy remains hollow. The 2025-26 Union Budget has proposed vocational laboratories in all secondary schools, but this will mean little if basic enrolment continues to decline.

Education Sector on Ventilator

The picture that emerges is troubling. India’s education sector appears to be on ventilator support, with declining enrolments, rising inequality, and parents deserting government schools. The government’s repeated invocation of India as a Vishwaguru contrasts sharply with the reality on the ground. A nation cannot teach the world if it fails to teach its own children.

The fall of 1.1 million students is more than a number. It represents dreams deferred, opportunities lost, and talent wasted. Policy makers can point to falling fertility rates or improved Aadhaar-linked data, but the truth is stark. Too many children are either not entering school at the right age or are dropping out too soon. The reasons range from migration to weak infrastructure to lack of confidence in government schooling.

For India to rise as an intellectual and cultural leader, it must first fix its own classrooms. Without urgent reforms in teacher quality, curriculum design, and public trust, the ambition of becoming a global guide will remain empty rhetoric. A strong education system is the foundation of national power. Today, that foundation looks shaky.