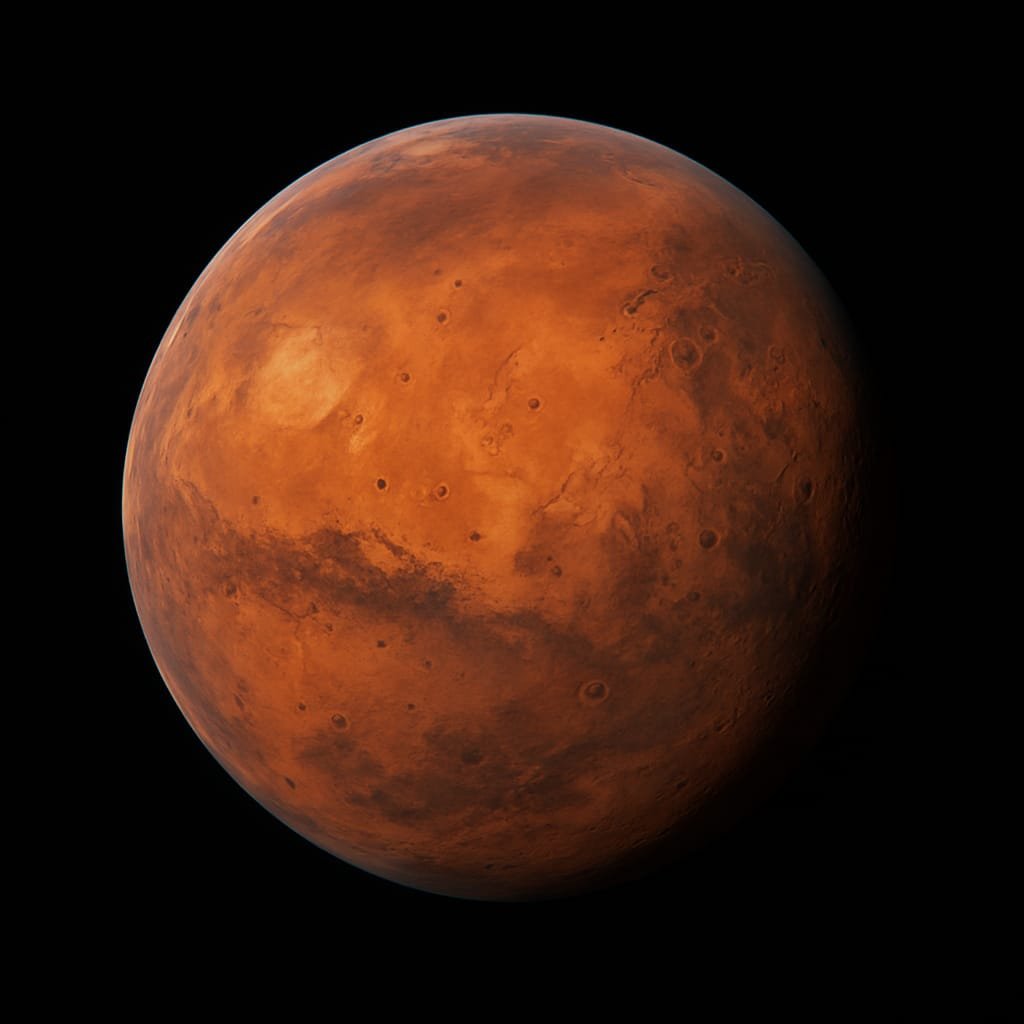

For decades, scientists have wondered: If Mars and Earth started off so similarly, why did one become a planet full of life and the other remain barren and dry?

A new discovery from NASA’s Curiosity rover might finally help answer this question. The rover has found something hidden deep in Martian rocks—carbonates, a type of mineral that may hold the key to understanding why water disappeared from the red planet and life never took root.

At first glance, Mars doesn’t seem all that different from Earth. Both planets are rocky, have polar ice caps, and even show signs that rivers and lakes once existed. Satellite images clearly show dried riverbeds and ancient lake basins. All this suggests that billions of years ago, Mars may have had the right conditions to support life. But somewhere along the way, things changed drastically.

The biggest missing piece in Mars’s puzzle is liquid water. While it has all the basic ingredients needed for life—carbon, energy from the sun, and some important minerals—it lacks the one thing that makes life possible on Earth: steady, flowing water. Scientists now believe that water on Mars was only temporary. It came and went in brief bursts, instead of sticking around long enough for life to form and evolve.

The rocks found by the Curiosity rover are rich in carbonate minerals. On Earth, carbonates such as limestone form when carbon dioxide from the atmosphere is absorbed into rocks and trapped there. This natural process plays a huge role in keeping Earth’s climate stable. Volcanoes release carbon dioxide into the atmosphere, and carbonates lock some of it back into the ground. This back-and-forth exchange helps maintain a climate that supports oceans, rivers, and rain.

Mars, however, seems to have had a very different experience. According to planetary scientist Edwin Kite, the lead author of a study recently published in the journal Nature, Mars had a “feeble” rate of volcanic activity compared to Earth. This means that less carbon dioxide was released back into the atmosphere after being trapped in rocks. As a result, Mars could not maintain a stable, warm climate. It cooled too quickly, and liquid water vanished.

Kite and his team used computer models to study what effect the carbonates might have had. They found that even when Mars had lakes and rivers, these “wet periods” were short-lived. Within 100 million years, they were followed by long stretches of extreme dryness. In cosmic terms, that’s not nearly enough time for life to evolve beyond the most basic forms.

This doesn’t mean all hope is lost. Scientists believe there might still be pockets of liquid water underground, hidden away in places we haven't explored yet. There could be “oases” where life might have survived—or even still exist. But these would be rare, not widespread.

The discovery of carbonate minerals changes how we think about Mars. It shows that the planet once had a way to trap carbon and possibly support water. But the system was weak and unstable. Without enough volcanic energy to keep the atmosphere thick and warm, Mars turned into a cold desert world.

This also helps us understand more about Earth. Our planet is not just lucky. It’s quite balanced. The carbon cycle, with the help of volcanoes and rocks, keeps conditions just right for life. Mars reminds us how fragile that balance can be.

In the end, Mars remained a desert because it couldn’t hold on to its warmth or water. Earth, by contrast, made all the right moves at just the right time—and that made all the difference.